Design Life-Cycle

assess.design.(don't)consume

Name: WaiHim Mok

Instructor: Christina Cogdell

Course: Des40A

Date: 12-11-2014

Condoms

Introduction

For centuries, humans have been fascinated with the ability to protect themselves from sexually transmitted diseases and the mechanisms for birth control. This figure has been rising over the years due to the sensitization on HIV, AIDs, and related venereal diseases (Rutherford). There have been a lot of campaigns on the same in the developed and developing nations popularizing the use of condoms across the globe. Currently, there are more than nine billion condoms that are used across the globe on a yearly basis. However, the figure could be higher, were it not for the various barriers that condom use faces among religious factions. Over the years of development, condoms have been made from various materials, such animal tissues, among them intestines, horns leather, and sheaths. At the same time, condoms have also been made from linen, silk paper and later in the mid 19th century, through better technologies, rubber/latex condoms are now common, with minimal variations (Schuster). The life cycle of a condom takes several turns, from the time it is purely chemicals to the time it is discarded after use or expiry (Khan).

Thesis statement: from the time that raw materials for the condom production are sources to the time that the condom is used or expired, there are health impacts to be wary of.

Condoms History

In the ancient ages much like today, people were still fascinated with the element of safe sex. The earliest form of a condom was used in Egypt, by a king called King Minos of Crete. The queen, who was called Pasiphae, had used a goat’s bladder to make sure that the semen from her husband would not harm her (Khan). Apparently, the king’s semen was made of serpents and scorpions, which had killed his mistress. As these condoms became common in Egypt, they would be colored with different colors to denote the social classes that used them. Majority of the Egyptians also thought that wearing the condoms would protect them from contracting bilharzias. Elsewhere in Ancient Rome, the Romans used the animal bladders not to prevent pregnancies, but to protect themselves from contracting venereal diseases. The Romans would treat the bladders with herbs to ensure their safety was guaranteed. In China, men would rap their penis with oiled silk papers, while the Japanese used tortoise shells as sheathes (Youssef).

Much of the development of a condom in Europe came in the sixteenth century, when syphilis became rampant. In 1564, Gabriel Falloppio, an Italian doctor, wrote that if a linen bag was dipped in salt solution or herbs, it would form a protective sheath. Linen and silk condoms became quite common in the 18th century as well as sheaths made from goats and lambs guts. A ribbon would be ties at the open end of the condom to prevent them from slipping during use (Schuster).

The latex condoms came much later in the 19th century, when Charles Goodyear came up with a way to process natural rubber. However, the rubber was too stiff when it was cold and became too soft when warm. At the same time, they offered the luxury of being long-lasting as they did not wear out as fast and they also extended as they were elastic (Youssef). For quite some time, there was not much change other than the fact that the rubbers that came much later did not deteriorate as fast. Later in the year 1995, America brought to the markets, the first plastic condoms some of which are still quite common. Rubber condoms have since undergone a lot of development what is available in the markets today.

Life Cycle

Manufacturing and the Components

The life cycle of a condom starts with the extraction of rubber latex from a variety of tropical plants. This milky fluid is actually formed of emulsions that are suspended in the sap water of the plants. To make sure that the emulsions are adhered together to form the latex paste, some chemicals are added to the latex sap. This is a process that is called compounding, which produces the paste that is later used in the condom manufacture (Worldwatch.org). The latex mixture is then mixed with several chemicals, and then milled to make sure that they achieve a particular particle size as a requirement. This mixture is then mixed with water and soap, a process that lasts about 24 hours. This mixture is then stored in to special drums where it matures for around ten days, during which time the temperature is regulated. At this point, the mixture has been compounded and is now ready for the dipping process (Stacey).

The dipping process is central to the condom manufacturing, where glass formers that are mounted on an endless chain are now dipped into the latex mixture. After the glass formers have been dipped for the first time, they are given time to dry after which they are then dipped into a second tank and again given time to dry. The glass formers with the latex are then taken to the vulcanization tunnels where they heated to about 115 degrees (Stacey). the formers are then dipped into the leach tanks where the condoms are brushed off and then they formers are cleaned ready for the next production.at this point the condoms are ready for the washing stage.

After the condoms are removed from the formers, they are powdered and washed in the washing machines, which are of the industrial grade. The condoms are powdered to ensure that they do not stick together and affect their quality (Worldwatch.org). They are span to dry and later on tumble dried to make sure that there is no water left inside or even humidity. They are then heated at 110 degrees to ensure all the humidity is cleared and they continue with the vulcanization process. After they are dried they can they be tested for faults (Cpr-germany.com).

The testing process uses electricity and conductivity principles. The condoms are pulled over mandrels made of metal and then moved passed conductive rubber at 2000 volts (Stacey). Ideally, a perfect condom that does not have holes on it will not conduct electricity and thus if there is no reading it is deemed fit for use. If the condom shows a reading it is rejected, while those that do not are taken to the foiling machine. At the foiling machine, the condoms are put in foils after lubrication and printing of the expiry dates on the foils. The condoms in their foils are then put in the consumer boxes and their batch numbers together with their expiry number printed on the top. After the final checkup from the bath numbers that boxes are then dispatched to the consumers (Worldwatch.org).

Impacts along the life cycle

Among the chemicals that are used on the lubricants of some of the condoms is benzene. While not many condom manufacturerswill admit to using it, it is found in quite a number. This has been found to be a chemical toxin that actually aids in the spread of the HIV and other venereal diseases as commonly cited with sexual lubricants used mainly by the gay partners (DW.DE). The chemical toxin has been found to be carcinogenic, poisonous when inhaled, irritant to the eyes among others. Its effects are quite slow most of the time but the effects are devastating. This is both dangerous for both the staffs working at the factories and the users at home.

Some of the people in the population are also allergic to latex. This means that if they use the latex condoms, they get a reaction from the contact. Although the condoms are made with part of the reason being talking the HIV scourge, these irritations by the latex may lead to increased chances of contracting the same. These effects are mostly on the consumer markets, which is generally at the stage of use along the cycle (Sirrichards.com).

Some of the latex condoms are made with compound that contains casein. This is a milk protein, which makes it an animal product. Some of the people in the population are vegetarian, which means using these products goes against their code of conduct as relates to animal treatment (Cpr-germany.com). While most of them use the condoms, very few understand the manufacturing process, making it a violation for the manufacturers that do not indicate the source of their raw materials.

Some of the consumers prefer the use of condoms that have spermicides as a protective measure against pregnancies (Worldwatch.org). Majority of the condoms that have the spermicides contain a compound known as nonoxynol-9.This is a compound that is effective when killing the sperms, but when used to regularly it leads to inflammation of the vagina and the cervix with the potential of actual damage to either. It can also lead to urinary tract infection and sexually transmitted diseases.

Parabens that are used in the lubricants of the condoms are effective in deterring microbial growth. However, they also tend to act as estrogens do bonding to the estrogens receptors. They have previously been found in cancerous cells removes from breasts. As such they have been found to be endocrine disruptors, with increased chances of cancer development.

Conclusion

The condom is one of the greatest inventions that ever graced the era of civilization. It is has had massive benefits to people across the globe (Rutherford). With the scourge of HIV and other venereal disease as well as the aspects of avoidable pregnancies, condoms have massive impact on the social circles. One of the lesser discussed issues, relates to their health impacts. Some of the chemicals that are used in the manufacturing process which is part of the product cycle, have detrimental health impacts some of which are down played for the benefits accrued in other areas (Byrnes).The impact of these chemicals relative to the level of use in the population is crucial and should be considered in light of public health.

Workscite

Byrnes, Stephen C. 'Dangerous Toxic Chemicals - Condom Lubricants - Health Report'. Health-report.co.uk. N.p., 1997. Web. 9 Dec. 2014.

Cpr-germany.com,. 'Production & Quality – Condoms, Condom Production, Machines For Condom Production &Ndash CPR Production And Distribution Company'. N.p., 2014. Web. 9 Dec. 2014.

DW.DE,. 'German Study Says Condoms Contain Cancer-Causing Chemical | Germany | DW.DE | 29.05.2004'. N.p., 2014. Web. 9 Dec. 2014.

Khan, Fahd et al. “The Story of the Condom.”Indian Journal of Urology : IJU : Journal of the Urological Society of India 29.1 (2013): 12–15. PMC.Web. 9 Dec. 2014.

Rutherford, George W. "Condoms in Concentrated and Generalised HIV Epidemics." The Lancet 372.9635 (2008): 275-6. ProQuest.Web. 9 Dec. 2014.

Stacey, Dawn. 'What Are Condoms Made Of?'.About.N.p., 2014. Web. 9 Dec. 2014.

Sirrichards.com,. 'Natural Latex Can Be An Answer To Condom Allergies | Sir Richard's'. N.p., 2014. Web. 9 Dec. 2014.

Schuster, Mark A., et al. "Student's Acquisition and use of School Condoms in a High School Condom Availability Program."Pediatrics 100.4 (1997): 689-94. ProQuest.Web. 9 Dec. 2014.

Worldwatch.org,.'Life-Cycle Studies: Condoms | Worldwatch Institute'.N.p., 2014. Web. 9 Dec. 2014.

Youssef, H. “The History of the Condom.” Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 86.4 (1993): 226–228. Web.

Gloria Marin

Professor Cogdell

DES 040A

11 December 2014

Energy in Condom Production

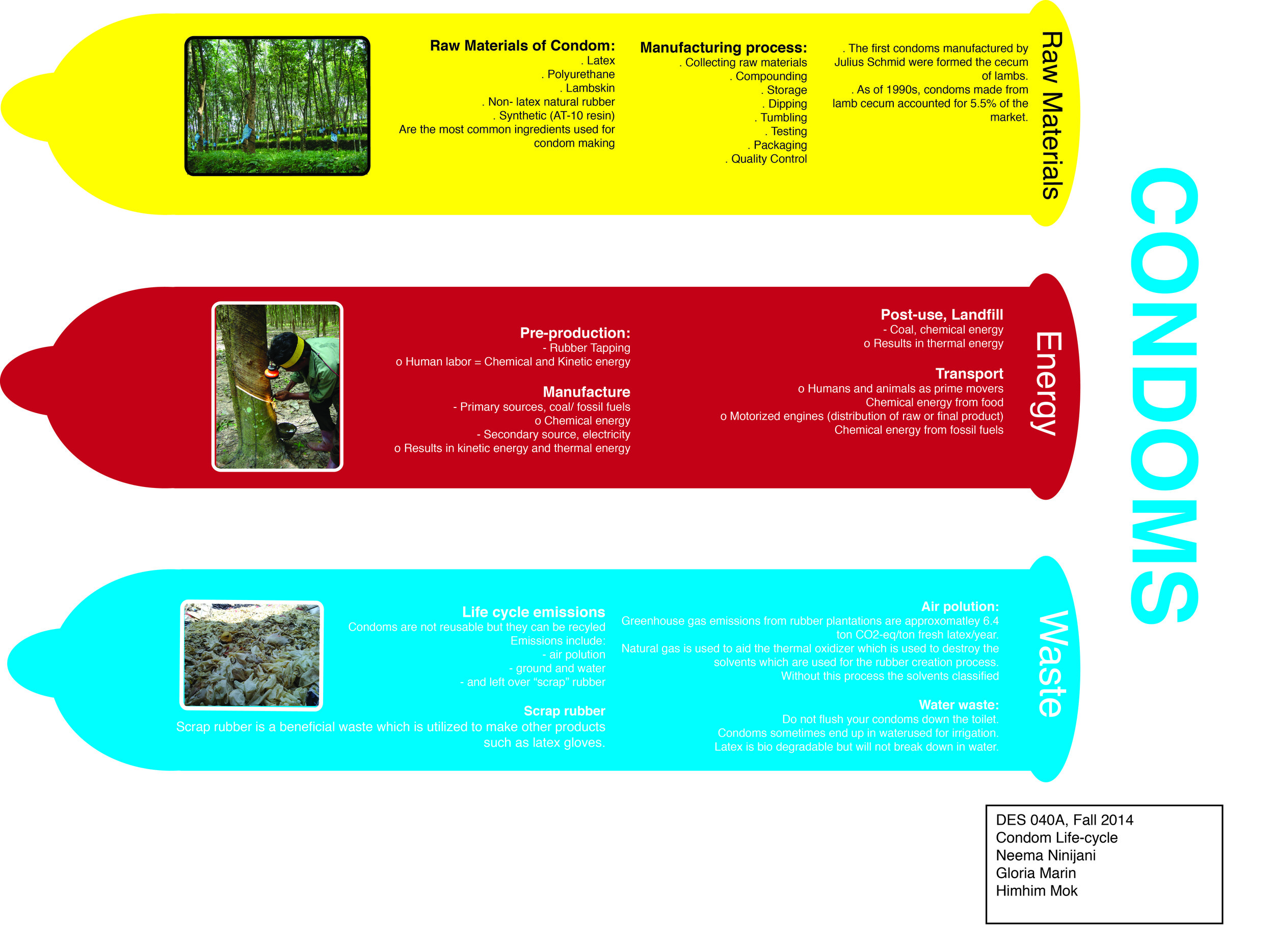

The concept of embodied energy is one takes into account the entire lifecycle of a product. This means examining the energy exerted during the collection of raw materials, the processing, which can entail physical and chemical changes to the raw materials, the transportation throughout the entirety of the product’s life-cycle, which can take place during the collection of raw materials, the shipping of the finalized product from the factory, and the movement to a landfill after the product’s use, and the final stage of the life-cycle, which is its disposal. This essay intends to examine all of those stages in the lifecycle of a condom, to attempt to create a comprehensive image of the embodied energy of this product.

It must be noted, however, that the energy density is limited due to the relatively bare research available regarding the energy used in the life-cycle of a condom. The great majority of research regarding condoms is related to their role in population growth and their efficacy in terms of contraception. Seeing as this essay’s focus is not one of social issues regarding population growth or a review of a condom’s effectiveness, that research is ill-fitted. This led me to widen my research to the energy used in the production of latex, one of the primary materials used in the manufacture of condoms, and rubber, a similar raw material that latex is derived from though processing.

Another limitation of this essay is that of the lack of statistical data regarding the energy used throughout the condom‘s life-cycle, something that is unsettling given the nature of the information age and its great access to type of research. It was difficult to find sources that discussed energy consumption beyond the type of energy used, and even some of that information was assumed to continue with the research of this product. Because of this lack in sources, a quantitative measure of the embodied energy of a condom was not possible. Instead, this essay will focus on the prime movers involved in the process and the types of energy that can be identified throughout the life-cycle.

The fist part of the life-cycle of a condom is, of course, the collection of the raw materials. The scope of this will envelope the collection of the primary raw material: latex, though its raw form is rubber. Most rubber plantations are found in Asia, specifically Malaysia, Indonesia and Thailand (The Condom). These rubber plantations rely heavily on a human labor force as a prime mover, which means that the primary energy sources are chemical; the food that the workers of these rubber plantations eat is the source of chemical potential energy that, when metabolized, can be transformed into kinetic energy used in the collection of the rubber. This also holds true for other steps in the condom’s life-cycle that involves human labor, though perhaps not so intensively. The collection of raw materials also entails its transportation to a processing plant, and later to the factory where it will be transformed into the final product, but transportation as a whole will be discussed later in the essay.

Processing and manufacture of the raw materials into a condom comprise the second portion of a condom’s life-cycle. It will be assumed, for the sake of the continuation of the examination of the product’s embodied energy that the site at which this processing and manufacture occurs is largely run on electricity. This assumption is based on the wide availability of this secondary energy source. Secondary because electricity is most often generated at power plants fueled by coal or other fossil fuels, which raises the issue of inefficiency due to the loss of energy in transfer from one form to another, e.g. fossil fuel to electricity. The wide availability of electricity is a result of its integration to infrastructure and its popularity that dates to the last century.

According to Robert L. Bebb, the main stages in rubber processing are as follows: mastication, vulcanization, and extrusion and calendaring. The first stage, mastication, is the physical break down of the rubber, a process that, “renders the rubber more plastic and decreases its solution viscosity” (Bebb, 95). Such a process uses kinetic and thermal energy to break down the rubber, resulting in both a physical and chemical change. Vulcanization is a more chemical change that entails the treatment of the masticated rubber with sulfur, again, a process that requires high temperatures and thus, large quantities of thermal energy and fossil fuels to be used. Extrusion and calendaring is the brief exposure to heat and air, which is again the use of thermal energy (Bebb, 100).

After this processing, the latex is formed into a condom, tested for faults, and packaged (The Condom). Throughout these processes there will invariable be the use of kinetic, chemical and thermal energy expended though interaction of machinery and human labor, which leads to the shipping of the final product. The energy used during transportation should be of the same type, regardless of its order in the condom life-cycle. It is primarily fossil fuel based due to that source’s high energy density and easy mobility. It is used to ship things across the globe, whether a product is shipped by land, sea or air, fossil fuels are the dominant energy source that transforms chemical energy into kinetic, thermal and other types of energy used in the transportation process.

The final stage in the life cycle of a condom is the disposal. The most common destination for a disposed condom is a landfill, where it will most likely be incinerated, and can create steam or electricity to be used as energy (The Condom). This is the obvious use of thermal energy, most likely as a result of the burning of coal or another fossil fuel.

Though no quantitative amount can be signaled, it is evident that fossil fuels comprise a large part of the energy in the life-cycle of a condom. The collection of raw materials, however, relies heavily on humans as prime movers making that stage in the life-cycle less dominated by fossil fuels, if the line is drawn at the human labor and the fossil fuels used to grow and harvest the food that these workers eat is ignored. The rest of the components of the life cycle, especially transport, which use fossil fuels most directly, and manufacture, which use electricity as a secondary source produced by fossil fuels, all actively incorporate the use of fossil fuels as a main energy source.

Works Cited

Bebb, Robert L. “Chemistry of Rubber Processing and Disposal.” Environmental Health Perspectives, Vol. 17 (Oct., 1976), pp. 95-102. JSTOR. Web. 30 Oct. 2014.

Garvey, B. S. “The Centenary of the Discovery of the Vulcanization of Rubber.” The Scientific Monthly, Vol. 50, No. 3 (Mar., 1940), pp. 278-282. JSTOR. Web. 30 Oct. 2014.

"THE CONDOM." Condomerie. N.p., (Jul., 2010). Web. 11 Dec. 2014.

Keddie, Joseph L., and Alexander F. Routh. Fundamentals of Latex Film Formation. Dordrecht: Springer, 2010. Print.

Mansor, Halimahton and M. D. Morris. “PRELIMINARY ANALYSIS OF YIELD AND COMPOSITION OF LATEX FROM ALSTONIA ANGUSTILOBA.” Journal of Tropical Forest Science, Vol. 2, No. 2 (December 1989), pp. 142-149. JSTOR. Web. 30 Oct. 2014.

McGinnies, W. G. and Arthur M. Bueche. “Natural Rubber Production.” Science, New Series, Vol. 192, No. 4239 (May 7, 1976), p. 506. JSTOR. Web. 30 Oct. 2014.

Meinhardt, Theodore J., et al. “Epidemiologic investigations of styrene-butadiene rubber production and reinforced plastics production.” Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health, Vol. 4, Supplement 2. Proceedings of the International Symposium on Styrene: Occupational and Toxicological Aspects (1978), pp. 240-246. JSTOR. Web. 30 Oct. 2014.

Raver, Paul Jerome. “Municipal Ownership and the Changing Technology of the Electric Industry: Trends in Use of Prime Movers.” The Journal of Land & Public Utility Economics, Vol. 6, No. 3 (Aug., 1930), pp. 241-257. JSTOR. Web. 30 Oct. 2014.

Schery, Robert W. “Manicoba and Mangabeira Rubbers.” Economic Botany, Vol. 3, No. 3

(Jul. - Sep., 1949), pp. 240-264. JSTOR. Web. 30 Oct. 2014.

Twiss, D. F. “II.—RUBBER LATEX AS A MANUFACTURING MATERIAL.” Journal of the Royal Society of Arts, Vol. 83, No. 4324 (OCTOBER 4th, 1935), pp. 1075-1091. JSTOR. Web. 30 Oct. 2014.

Neema Ninijani

Professor Cogdell

DES 040, Fall 2014

12/10/14

Male contraceptives have been used as far back as the ancient egyptians. Today, condoms are one of the most popular and effective forms of birth control. Latex is the most prominent material used to produce condoms. The lifecycle of a latex condom begins with the procuring of its source and ends in its degradation. The emissions produced from the creation of latex products include air , ground, and water waste.

Condoms have been one of the most successful forms of contraception next to abstinence and reproductive surgery. Many of the early condoms which can be found in literature were made from animal intestine “A Persian 'Kendu' or 'Kondu' as the source of the word,which means a long storage vessel made from animal intestine”(13). Animal intestine condoms were ineffective in providing protection from sexually transmitted diseases. Once the rubber vulcanization process was created, condoms began to be produced with rubber materials. “ The introduction of liquid latex in the mid 1930s made it possible for greater tensile strength”(3). With further advancements condoms became more popular in production. The AIDs epidemic and proper sexual education has made the male condom a common item for responsible sexual activities.

The waste produced by a condom does not begin once an individual disposes a condom after use, but it begins from it’s production. Condoms are produced in a variety of materials all of which require different processing and production methods, the main materials used in condoms are natural rubber latex, synthetic polyurethane, and lambskin. Latex is the most popular. There are greenhouse gas emissions which are created from latex procurement and production. Carbon was found to be a significant emission from rubber facilities. “Fossil fuels are used by tractors during land preparation for activities such as plowing and fertilizing, during the felling of rubber trees at wood harvest and during land clearing by chainsaws and by truck transporting logs from the rubber tree plantation at age 25 years. The volume of diesel consumption by tractors during land preparation was obtained from the field surveys and TRF (2007). Consumption ranged from 56.25 to 92.75 L ha−1. In this study, an average value of 70.08 ± 16.16 L ha−1 was used. The emissions from diesel production and use were 8.21 and 54.28 kg carbon equivalent ha−1 (C-e ha−1), respectively. During 1990 to 2004 the yearly average value was 9342.37 ± 2992.92 t CO2-e” (11) . Also fossil fuels were used for disposal of certain chemical solvents. The natural gas is used as an oxidizer. Also ammonia is used as a binder of the latex. Ammonia is used to prevent latex coagulation. “We estimate greenhouse gas emissions from RSS to be relatively low: 20 kg CO2-eq/ton RSS. This is excluding CO2 from biomass combustion (∼100 kg CO2-eq/ton RSS), because the wood used as fuel for drying and smoking the rubber sheet is from trees that are likely replanted”(12). These methods are harmful to the environment and to the workers in the rubber plantations.

The method’s of condom disposal also play a huge part on a condom’s effect on the environment. Both ground and water waste are produced from improper disposal of condoms. Many people tend to flush their condoms down the toilet which results in contaminated water. “You can find condoms and tampon applicators on the fields where reclaimed water is used to irrigate”(3). If people were to dispose of condoms properly they would be less harmful to the environment. Latex and lamb condoms are biodegradable and will cause degrade if the end up in a landfill.

The carbon footprint produced throughout a condoms lifecycle is miniscule as opposed to the carbon footprint produced by a human consumer. Condoms from a certain perspective are also effective at slowing negative environmental impacts due to overpopulation. “It should be noted that using a condom far outweighs its negative impact on the environment by blocking the chance for reproduction, something that nearly doubles if not triples, maybe even quadruples, your carbon footprint in the world by spawning another cute, little, rambunctious consumer”(5). Sam Goering brings up a fair argument, human consumers are creating a large part of our environmental impacts. Just as we should consume responsibly we are given the responsibility of reproducing responsibility.

There are varying forms of waste created throughout a condoms lifecycle. a A condom’s emissions are not as significant as the benefits it provides. It was difficult to find information provided by condom manufacturers themselves. One wonders if such a beneficial product has a darkside. People who take the responsibility to engage in safe sex should also take the responsibility of properly disposing of their condoms.

Works Cited

1.G Mathewa, R.P Singhb, N.R Nairc, S Thomasd Polymer Volume 42, Issue 5, March 2001, Pages 2137–2165

2. Jonathan Winfield, Ioannis Ieropoulos, Jonathan Rossiter, John Greenman, David Patton ,Biodegradation and proton exchange using natural rubber in microbial fuelcells.November 2013, Volume 24, Issue 6, pp 733-739

3.Mary Feronia. Condoms: Don’t Flush ‘Em! http://www.feroniaproject.org/condoms-dont-flush-em/. November 15 2011

4.“Alice”. Environmentally-friendly condom disposal, http://goaskalice.columbia.edu/environmentally-friendly-condom-disposal. December 20, 2002

5.Sam Goering. HARD-TO-RECYCLE ITEM #1: CONDOMS, http://www.pickupamerica.org/blog/guest/hard-recycle-item-1-condoms. January 27, 2010

6.Robert L. Bebb. Chemistry of Rubber Processing and Disposal- Environmental Health Perspectives, Vol. 17, (Oct., 1976), pp. 95-102.Published by: Brogan & Partners

7.McNeill ET; Gilmore CE; Finger WR; Lewis JH; Schellstede WP.The latex condom: recent advances, future directions.Research Triangle Park, North Carolina, Family Health International

8.Unnamed. The Second E: Ecological Reasons to Use NFP, http://ginnieree.wordpress.com/2014/06/08/the-second-e-ecological-reasons-to-use-nfp/. June 8, 2014

9.Ben Block. Life-Cycle Studies: Condoms, http://www.worldwatch.org/node/6462. worldwatch@worldwatch.org 1400 16th St. NW, Ste. 430, Washington, DC 20036

10.Jennifer Newton. Condom Fishing. http://prospect.rsc.org/blogs/cw/2013/10/22/condom-fishing/ . Tue 22 Oct 2013

S. Petsri, A. Chidthaisong, N. Pumijumnong, C. Wachrinrat, Greenhouse gas emissions and carbon stock changes in rubber tree plantations in Thailand from 1990 to 2004, Journal of Cleaner Production, Volume 52, 1 August 2013, Pages 61-70,

Warit Jawjit, Carolien Kroeze, Suwat Rattanapan, Greenhouse gas emissions from rubber industry in Thailand, Journal of Cleaner Production, Volume 18, Issue 5, March 2010, Pages 403-411, ISSN 0959-6526, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2009.12.003.

H Youssef. The History of the condom. ournaloftheRoyalSocietyofMedicine Volume86 April1993