Design Life-Cycle

assess.design.(don't)consume

Marlen Guzman

Cogdell

DES 40A Section 2

09 Dec. 2014

Tiffany Diamond Ring: Raw Materials

People living in New York City during the 1830’s were in the right place at the right time, especially if they had a business idea and a little bit of extra money. At the age of 25, Charles Lewis Tiffany and John B. Young opened a small emporium for stationary and fancy goods in Lower Manhattan. Taking control of the store and redirecting the firm’s emphasis to mainly sell jewelry, Charles Tiffany renamed the company “Tiffany & Company” in 1853. (Tiffany & Co History 1). Ever since then, Tiffany & Co. has been one of the most well-known jewelers from opening nearly one hundred stores in the United States alone to even trademarking their company’s signature color “Tiffany Blue”. Being as successful as Tiffany & Co. is, it would only make sense to think that their popularity is due to the company making their jewelry in a significantly different and better way. However, seeing the processes and materials Tiffany uses to make their rings and researching how most other jewelers mine and manufacture their rings, it is evident that there is mainly one way to make diamond rings: out of diamonds. Most, if not all, companies mine for platinum and diamonds, cut the diamonds, cast and mold the platinum, and finally place the cut diamonds into the platinum ring. The making of diamond rings is an extremely top heavy process and does not vary from company to company; however, what does differentiate Tiffany & Co. rings from other jewelers is the advertising and glamour the public associates with receiving the classic and well-known “little blue box.”[1]

One of the few main materials needed in order to make a diamond ring is platinum. Platinum does not corrode or rust over time and keeps a nice silver/grey shine for years. Because of platinum’s resistant and beautiful qualities, it is widely used in the jewelry market because it stays looking brand new virtually forever and compliments the shine of a diamond well. Tiffany & Co. receives all of their platinum through a separate company specializing in mining called Stillwater Mining Company. They mine and process their platinum ores (as well as palladium ores) in underground mines in south-central Montana. They are also the only known mines that hold significant amounts of platinum group metals (PGMs) in the United States. Platinum is usually a by-product of nickel and copper mining and processing and is collected when platinum settles to the bottom of a cell during the electro-refining process of copper. However, there is another way to collect platinum, which is to find pure platinum in placer deposits and/or other ores and then remove the impurities that float to the top of the liquid since platinum is far denser than the impurities usually mixed with it. (Heiserman 272–274). I was unable to find out which way Stillwater Mining Company finds and filters the platinum out, but I would infer that they use the second method since their website said that their mines are PGM-rich.

Diamond Raw Material:

Next comes finding and mining for diamonds. It is widely thought that diamonds are made up of pressurized coal. However, this theory is false. “Geologists believe that the diamonds in all of Earth's commercial diamond deposits were formed in the mantle and delivered to the surface by deep-source volcanic eruptions. These eruptions produce the kimberlitic and lamproite pipes that are sought after by diamond prospectors. Diamonds weathered and eroded from these eruptive deposits are now contained in the sedimentary (placer) deposits of streams and coastlines.” (“How Do Diamonds Form?” 1). Since the formation of natural diamonds needs great pressure and heat, they form in limited zones of Earth's mantle about 90 miles below the surface where temperatures are at least 1050 degrees Celsius whereas coal forms at 2 miles below the surface at most. The diamonds are then extracted from the ground in large chunks of rock.

It was difficult to find out Tiffany’s diamond source countries, but my partner and I found them since these are where most diamond jewelers receive their diamonds from the same countries. Some of these countries include Australia, Botswana, Canada, Namibia, Russia, Sierra Leone, and South Africa. (Living Up to Diamonds: Report to Society 2013 2). It was impossible to find out exactly where Tiffany & Co. gets most of their diamonds from, but we thought their diamonds came from somewhere in Africa, since the majority of the listed source countries are there. Also, we ruled out Australia, since the main diamond mine there produces mostly brown diamonds.

Manufacturing

After mining for diamonds and platinum, there are basically no new materials being added to Tiffany & Co. diamond rings. However, preparing the diamonds is the most crucial part to making the ring because the process must be done carefully and correctly in order to provide the best possible product. There are four steps in manufacturing and preparing the diamond for the ring.

The first step is cleaving; this is cutting rough diamonds down to a manageable size by placing the diamond in a quick-drying wax mold to hold it in place. The cutter then cuts a groove into the diamond (on its weakest point) with a laser, puts a steel plate into the groove and forcefully hits the diamond, splitting it in two.

Next comes sawing; the cutter saws the diamond using a phosphor-bronze blade rotating at about 15,000 rpm. Lasers can also be used to saw diamonds, but the process takes hours. During the sawing step, the cutter decides which parts of the diamond will become the table (the flat top of the stone with the greatest surface area) and the girdle (the outside rim of the diamond).

Then, he proceeds to the third step which is bruiting/cutting. This technique gives diamonds their shape. When diamonds are cut by hand, the technique is called bruiting (cutting refers to bruiting by machine). When the cutter shapes diamonds by hand, he relies on the diamond's hardness as his tool and uses diamonds to cut diamonds. He uses a small, stick-like instrument with a cement-filled bowl at the tip to hold the diamond. The diamond is inserted in cement with just one corner exposed. Using one of these sticks in each hand, the cutter rubs the exposed diamond parts together to bruit them.

Finally, the last step is polishing the finished diamond. To create the diamond's finished look, the cutter places it onto the arm above a rotating polishing wheel. The wheel is coated with an abrasive diamond powder that smooth’s the diamond as it is pressed against the wheel (Bonsor 1-8).

The other part of manufacturing diamond rings is casting and molding the platinum to make the actual ring. The most common and easy way to cast and mold the platinum is using a “lost wax casting system.” This is easy because once one mold is created it can be used over and over again. Using wax, a prototype of the ring is formed and is placed in a mold box, which is then filled up with liquid rubber/silicone compound. After, the wax ring is removed and the cavity inside the rubber is a perfect copy of the master copy and can be used as a mold for the next platinum rings. (“Lost-wax Casting” 1-2).

Once the platinum has solidified, the next step is fitting the diamond onto the ring. This part of the process can take professionals weeks to perfect since setting the diamond on the ring is crucial to the aesthetics of the ring because having the diamond elevated on the holders allows for more light to pass through it from underneath giving the illusion of more shine. (“Model the Ring” 3).

Distributing/Transportation

After the manufacturing process, there really aren't any other raw materials contributing directly to the ring itself. However, the materials travel long distances from the mines in Africa and Montana to getting the materials to Rhode Island and New York where the jewelers, polishers, and stone setters are located. This means that a large amount of raw materials are being used as fuel to transport the diamonds and platinum and must be recognized as a large raw material itself. Tiffany does not directly state their means of transportation, but I can infer that air cargo planes ship the diamonds from Africa to the United States, and semi-trucks ship platinum from Montana to Rhode Island and New York.

The planes’ main energy source/fuel is jet fuel. Jet fuel is made up of Kerosene, which is made up of petroleum chemicals from deep within the Earth. In order to manufacture Kerosene, several steps must be taken. The basic process is extracting crude oil from the ground, separating the oil from all other impurities, distilling the oil and separating it by densities. Once the oils are distilled, the oil is further processed with chemical reactions in order to make Kerosene, which then gets added into a mixture of other oils in order to manufacture jet fuel (“Kerosene” 1).

Besides jet fuel, the other raw material in transportation is fuel used in shipping trucks. Most shipping trucks that transport within the U.S. generally run on petroleum diesel gas. This fuel is relatively dense and oily [since] it is composed of a blend of different types of hydrocarbons. One of the main components addressed by governments is sulfur, which can lead to very harmful emissions when the fuel is used. In modern times, much of the diesel sold in the US and EU is Ultra-Low Sulfur Diesel (ULSD), which has most of the sulfur removed (“What Is Diesel Fuel?” 1). Like Kerosene and other products made from fossil fuels, diesel is basically made from distillation of crude oil.

Looking at the raw materials for Tiffany diamond rings was an eye-opener because of the immense energy used during the process. The making of a diamond ring does not stop at the diamonds and platinum that are what physically makes up the ring. Researching this process of the raw materials it takes to make a small band on one’s finger makes me realize that we should all be paying more attention all the energy necessary to make the products we all know and love. Perhaps in the case of Tiffany, as well as other diamond rings, since they are all basically made of the same materials anywhere we may look, we might feel more inclined to purchase the ring regardless of the energy seeing that its sentimental value for many people is worth more than the cost it took to make it. Ending on this optimistic note, fortunately, diamond rings are not objects that get wasted. However, diamond rings are objects that get passed down for many generations or get recycled into a new piece of jewelry that will also not be thrown away.

Works Cited

“About Tiffany & Co.” Press.tiffany.com. T&Co., n.d. Web. 08 Dec. 2014

Bonsor, Kevin. "How Diamonds Work." How Stuff Works. HowStuffWorks, n.d. Web. 28 Oct. 2014.

Heiserman, David L. 1992. Exploring Chemical Elements and Their Compounds. N.p.: TAB, 1992. 272-74. Print.

"How Do Diamonds Form?" Geology.com. Geology.com, 2014. Web. 08 Dec. 2014.

"Kerosene." Madehow.com. Advameg. Inc., n.d. Web. 09 Dec. 2014.

Living Up to Diamonds: Report to Society 2013. London: De Beers Group of

Companies, 2013. Print.

"Lost-wax Casting." Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, 5 Nov. 2014. Web. 08 Dec. 2014.

"Model the Ring." Instructables.com. Autodesk. Inc., n.d. Web. 08 Dec. 2014.

Our Essential Commitments: 2012 Corporate Sustainability Report. Billings: Stillwater Mining Company, 2012. Print.

"What Is Diesel Fuel?" WiseGEEK. Conjecture Corporation, 2014. Web. 08 Dec. 2014.

[1] The little blue box is made of dyed cardboard. See past project on cardboard for details on the materials/making of cardboard.

Katherine Erickson

Christina Cogdell

DES 40A

9 December 2014

Tiffany Diamond Ring Waste/Emissions

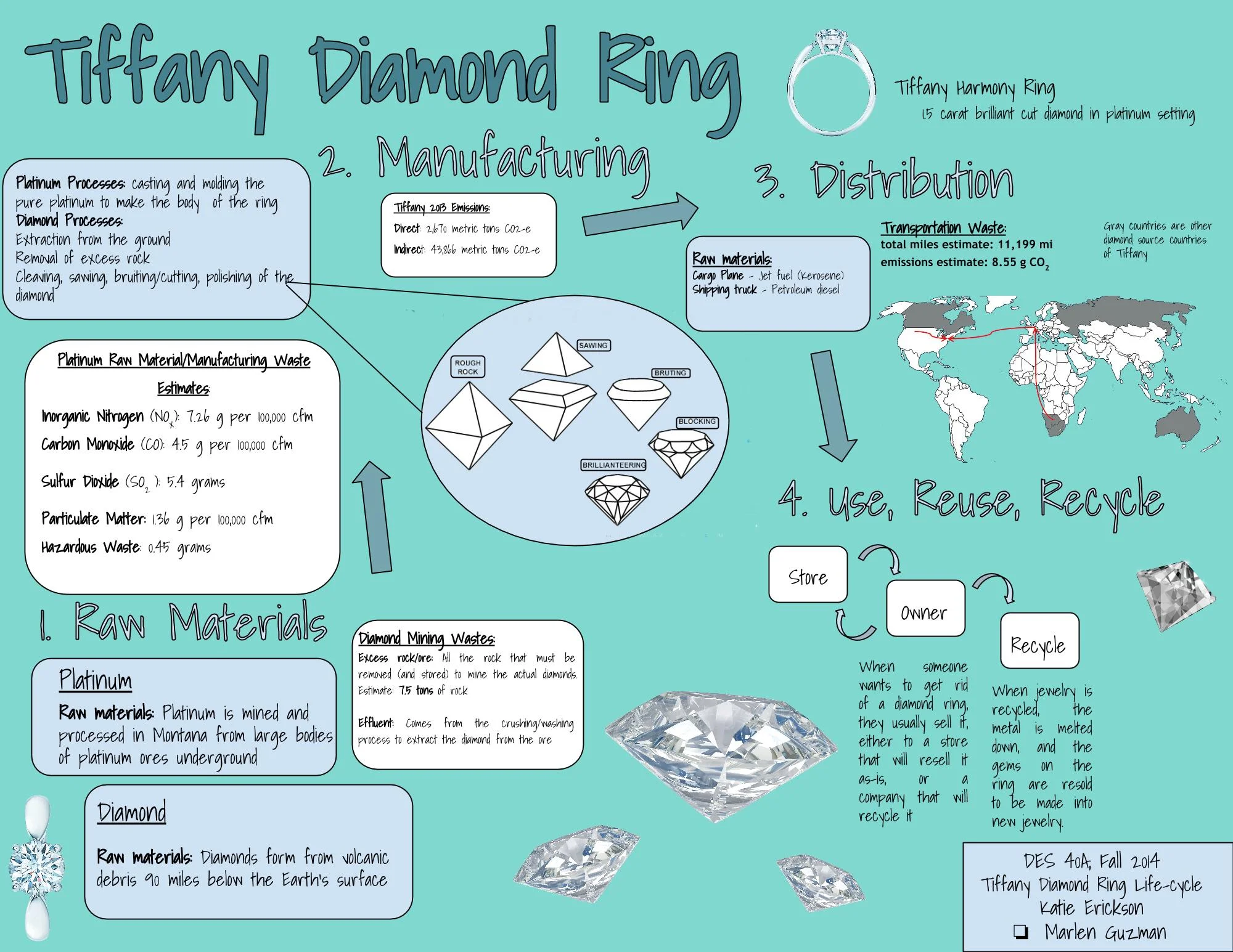

The iconic Tiffany Blue Box is known for holding exquisite pieces of jewelry, but what goes into those pieces extends far beyond the lid. The process of making a piece of jewelry is global, and the waste generated is very large for something so small. The lifecycle of a diamond ring is very front loaded, meaning that most of the materials, energy, and waste are generated in the beginning stages of the lifecycle. The raw materials acquisition and manufacturing are particularly intensive, and since diamond rings are so valuable, there is little waste management other than that associated with the beginning stages. The specific Tiffany piece we chose to focus on is the Tiffany Harmony ring—a simple but classic diamond ring with a brilliant cut diamond in a platinum setting.

The two main raw materials in the Tiffany diamond ring we looked at are platinum for the band, and the diamond itself. But while the number of raw materials is small, the process and waste accumulation during the process is quite large. For the simple ring we looked at, we assume it contains roughly five grams of platinum (since it will vary some based on ring size). Tiffany states that 65% of the platinum they use comes from the Stillwater Mining Company in Montana, so we also assume that the platinum in the ring comes from here (Our Essential Commitments: 2012 26). Stillwater’s 2011 production was 119,000 ounces of platinum, so the five gram estimate represents .00015% of the yearly production, which is used to make estimates for waste generation of a single ring’s worth of platinum (Our Essential Commitments: 2012 5). The platinum mining process creates various types of waste that include inorganic nitrogen, carbon monoxide, particulate matter, sulfur dioxide, and “hazardous waste”. Inorganic nitrogen is an air and water pollutant, and the Stillwater mine in 2011 generated 1.2 lbs/hr per 100,000 cubic feet per minute (cfm) of inorganic nitrogen. Using the percentage of yearly production for the five grams of platinum, an estimate of 7.26 grams per 100,000 cfm of inorganic nitrogen is produced in extracting and processing 5 grams of platinum. A similar calculation is used for the other types of emissions covered by Stillwater mine. By these standards, processing five grams of platinum also emits 4.5 g per 100,000 cfm of carbon monoxide (a poisonous gas), 1.36 g per 100,000 cfm of particulate matter (small dust-like particles that can affect air quality), approximately 5.4 g of sulfur dioxide from the smelting process, and approximately .45 g of “hazardous waste” (Our Essential Commitments: 2012 15). This is somewhat hard to decipher with no comparison, so it is worth noting that these emission rates are well below federally regulated limits, but even the estimates for sulfur dioxide and hazardous waste alone are equal to more than the mass of the platinum being produced. The other quantities cannot be compared directly since they are in units of a rate and not a discrete amount.

The wastes from the diamond mining process are similar to those of the platinum mining process, but the information available tends to focus on different things. Tiffany sources their diamonds from a variety of countries all over the world (including Russia, Australia, and Canada), but the biggest source of diamonds likely comes from several African countries, particularly Botswana (Corporate Responsibility Report 2013 17). One of the largest by-products of any mining in general, but specifically diamond mining, is the excess rock that needs to be removed and stored. Kimberlite, which is the diamond ore, can be fairly deep in the ground resulting in many tons of excess rock need to be removed before the ore can be collected (Posukova, T. V., et al 96). Another similar waste is the excess ore, since diamond ore is by no means 100% diamonds. Usually the “richness” of a mine is estimated by the number of carats per ton of ore. A fairly average value is around one carat per ton, which is used to make estimates (Posukova, T. V., et al 96). The ring we focused on has a 1.5 carat stone, so it would have produced at least 1.5 tons of excess ore, plus the excess non-ore rock from the surface. With the assumption that there is twice the amount of excess rock to ore, the whole mining process produces 7.5 tons of excess rock and ore. The major environmental impact of such large amounts of rock is the space needed to store it. Rock storage increases the area the mine takes up and encroaches on the surrounding environment, and can negatively affect ecosystems in its vicinity (Posukova, T. V., et al 96). Besides just waste rock, De Beers—the diamond mining company associated with Tiffany—has put out estimates for another common measure of emissions, which is CO2 equivalent. This does not just measure CO2 emissions, but also “converts” other types of greenhouse gasses and sets them equal to an amount of CO2 that would have the same global warming effect, since certain gasses are much worse than CO2 with a global warming perspective. De Beer’s estimated in their corporate report that in 2013, their productions emitted 1.8 million tons in CO2-e. (Living Up To Diamonds 17). Scaling down to just the operations needed to produce the diamond in the ring—based again on percentage of yearly production—an estimated 86.7 tons of CO2-e were emitted for the 1.5 carats of diamond in the ring (Living Up To Diamonds 4). Another main waste/emission of the diamond mining process is the effluent, which is basically the wastewater that is discharged from mining facilities after the ore is crushed and washed to extract the rough diamonds. There was no concrete information on effluent discharges found, but it can be noted that certain wastewater treatment chemicals that can be found in effluent can potentially harm animals and ecosystems (De Rosemond and Liber).

When it comes to processing the raw materials, the platinum is mostly processed at the mine, since Stillwater has the facilities to smelt and extract the platinum, but the rough diamonds need to be cut and polished, and are sent to a facility before they make it to Tiffany’s manufacturing plant where the jewelry is assembled (“Mine Site Concentrators”). Locations of facilities and sources are important in determining approximations of emissions from transportation. Making a Tiffany diamond ring is a very global process. As mentioned before, much of their platinum comes from Stillwater mine in Nye and McLeod, Montana, and the main source of diamonds come from Africa—specifically Botswana (since Botswana produces 73% of De Beer’s African diamonds). Laurelton Diamonds, a subsidiary of Tiffany that polishes many of their diamonds, also has a large facility in Antwerp, Belgium—a location where an estimated 84% of the world’s rough diamonds pass through. Using an estimate of emissions for air cargo, 1.527 kg CO2 per Ton-Mile, along with the travel distance of roughly 5175 miles and the weight of 1.5 carats for the diamonds, the estimate comes out to equal 2.62 grams of CO2 emitted for this shipping route (“How We Calculate”). The diamond must also travel from Belgium to the manufacturing facility in Rhode Island, and the platinum must be transported from the mine in Montana to Rhode Island as well. Once the ring is assembled in Rhode Island, it goes to the distribution facility, and finally to the store. Since Tiffany’s flagship store is in New York, we use that as the store of choice. We also assume ground (truck) transport is used for land travel within the United States, which emits 0.297 kg CO2 per Ton-Mile. With all this to consider, an estimated 8.55 grams of CO2 are emitted from the transportation and distribution process.

So after the ring has been assembled, and made its way through the distribution center and into a store, the next step is for someone to buy it. In 2013, Tiffany’s direct CO2-e emissions from their stores were 2,670 metric tons (Corporate Responsibility Report 2013 47). But once the ring has been sold, due to its nature, there is comparatively very little that happens. The Tiffany name certainly has an effect on the likely outcome (and monetary value) of a ring like the one we looked at. The whole atmosphere Tiffany is surrounded with is meant to emphasize the prestige and superiority of owning a Tiffany diamond presented in its exclusive and iconic Tiffany Blue Box. Diamond rings in general tend to be kept for very long amounts of time—even lifetimes, where they are passed down to the next generation. But with a higher end ring like a Tiffany one, this effect is extended. Diamond jewelry seems in particular to hold more meaning and value than other gemstones. The world famous ad campaign “A Diamond is Forever” has certainly had its effect of the lifespan of a diamond ring, making them a staple almost for engagement rings (and certainly contributing to the monetary value). But sometimes circumstances come where the owner wishes to sell the ring. There are various types of places that will buy valuable jewelry. Smaller stores like pawn shops or jewelry stores will resell the jewelry as it is, but some larger companies dedicated to the task will recycle the jewelry. Metal can be melted down, so it has a very stable “melt value”. “About 27,700 kg of platinum was recovered from the jewelry industry globally, an increase of 10% compared with that of 2011” (qtd. in U.S. Department of the Interior 2). Diamonds however must stay in their “original” form to retain their value, and that value becomes more subjective, although diamond quality ratings (the 4 C’s) are an objective guide for diamond pricing. Cut diamonds can be resold and eventually made into new jewelry. White Pine Diamonds is a company that does this, removing, sorting, and reselling cut diamonds for manufacture in new jewelry (“White Pine Diamonds”).

So overall, the lifecycle of a diamond ring involves a lot of waste, and often it is difficult to visualize all of the waste that can be created in the process of making something that looks so clean cut. The life cycle is very condensed towards the beginning, since it takes a tremendous amount of effort to turn what are essentially rocks into a shiny ring, and while diamond recycling exists, advertising promotes a situation where every engagement ring features a brand new diamond unique to the individual couple. “A Diamond is Forever” focuses more on the idea that a diamond is bound to individual(s) forever rather than the idea that a diamond will last forever. It promotes new production of diamonds rather than their recycling—and the production of diamonds creates a lot of waste. When looking at the full picture of a Tiffany diamond ring, it can be surprising to see how much waste something so small and shiny can produce.

Bibliography

Bernick, Libby. "The True Cost of Your Engagement Ring." GreenBiz. Green Biz Group, n.d. Web. 7 Dec. 2014. <http://www.greenbiz.com/blog/2013/07/15/true-cost-jewelry-engagement-ring-metals-footprint>.

Bonsor, Kevin. "How Diamonds Work." How Stuff Works. HowStuffWorks, n.d. Web. 28 Oct. 2014. <http://science.howstuffworks.com/environmental/earth/geology/diamond3.htm>.

"Conditionally Exempt Small Quantity Generators." U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. United States Environmental Protection Agency, n.d. Web. 7 Dec. 2014. <http://www.epa.gov/osw/hazard/generation/cesqg.htm>.

Corporate Responsibility Report 2013. New York: Tiffany, 2013. Print.

De Rosemond, Simone J C, and Karsten Liber. "Wastewater Treatment Polymers Identified as the Toxic Component of a Diamond Mine Effluent." Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry/SETAC 23.9: n. pag. ProQuest Environmental Sciences and Pollution Management. Web. 7 Dec. 2014. <http://search.proquest.com/docview/66896191?accountid=14505>.

"Diamond Cutting Process." Chart. Diamond Guide Headquarters. Jewelery-Secrets.com, n.d. Web. 8 Dec. 2014. <http://www.jewelry-secrets.com/Diamond-Guide/Diamond-Cut.html>.

Environmental, Health, and Safety Guidelines: Base Metal Smelting and Refining. Ifc.org. International Finance, n.d. Web. 7 Dec. 2014. <http://www.ifc.org/wps/wcm/connect/4365de0048855b9e8984db6a6515bb18/Final+-+Smelting+and+Refining.pdf?MOD=AJPERES>.

"How We Calculate." Carbonfund.org. Carbonfund.org Foundation, n.d. Web. 7 Dec. 2014. <http://www.carbonfund.org/how-we-calculate>.

Living Up to Diamonds: Report to Society 2013. London: De Beers Group of Companies, 2013. Print.

"Mine Site Concentrators." Stillwater Mining Company. Stillwater Mining Company, n.d. Web. 28 Oct. 2014. <http://www.stillwatermining.com/operation/mine-site-concentrators.html>.

Our Essential Commitments: 2012 Corporate Sustainability Report. Billings: Stillwater Mining Company, 2012. Print.

Posukova, T. V., et al. "Diamond Industry Wastes: Mineral Composition and Recycling." Moscow University Geology Bulletin 68.2 (2013): n. pag. Print.

Rapaport Magazine. Martin Rapaport, n.d. Web. 7 Dec. 2014. <http://www.diamonds.net/Magazine/Article.aspx?ArticleID=30962&RDRIssueID=49>.

U.S. Department of the Interior. 2012 Minerals Yearbook: Platinum Group Metals [Advance Release]. By Patricia J. Loferski. N.p.: n.p., n.d. Print.

White Pine Diamonds Homepage. White Pine Diamonds. White Pine Trading LLC, n.d. Web. 7 Dec. 2014. <http://www.whitepinediamonds.com/>.