Design Life-Cycle

assess.design.(don't)consume

Bikesh Maharjan

Design 40A

Christina Cogdell

3/13/14

Raw Materials -Yulex R2 Front-Zip Full Suit Wetsuit

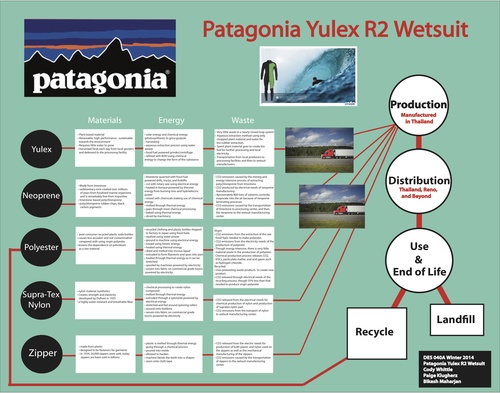

Wetsuits are protective garments worn by athletes that participate in any cold water sports; they provide warmth, durability and flex. In the year of 1951, “Physicist Hugh Bradner embarked on creating what would be the beginning of a highly successful product used around the world, the wetsuit.”[1] Wetsuits were predominantly made from foamed neoprene in the early 1950s. The design of the early neoprene wetsuits were “really uncomfortable and you got a lot of flushing”[2]. As the world’s technologies started to boom, machines easily made many of these products, materials transported from around the world, and easily produce without the human effort. In today’s world, many companies are looking toward making products that are eco-friendly, environmentally sustainable and that last longer. Wetsuit is also one of the products, which includes many materials like yulex Rubber, neoprene, recycled polyester, Supra Tex Nylon and Zipper combined together to provide warmth, strength, durability and sustainability to the customer.

Patagonia, an outdoor and sportswear company from Ventura, California, is one of the most well known companies which is committed in providing the customers with a product that is green friendly, less harmful to impacting the environment and that can be easily re-used in the future generation. In mid-November of 2012, Patagonia partnered with Yulex Corporation to create a new material that will be a true alternative to neoprene wetsuit. “After four years of working together, Patagonia and Yulex have co-developed a unique material that allows us to make a wetsuit that is 60% guayule (plant) based”. [3] But their goal is to reach 100% plant based material in the future and helping to reduce . Yulex Rubber, neoprene, recycled polyester, Supratex Nylon and zipper combined together to make wetsuit that provides for warmth, strength, durability and sustainability.

Yulex Rubber is made from a plant called guayule, which is grown in the southwestern part of the United States. It requires less water to grow and can be grown under arid and semi-arid climatic condition, uses no pesticides and has a very clean manufacturing process. Yulex Guayule is grown as a perennial crop, an agricultural strategy that reduces soil erosion and serves as a highly effective dust control tool.[4] Yulex guayule is harvested year-round after an initial maturation period of 18-24-months and a single crop are harvested annually year after year for up to five seasons.[5] Yulex’s process extracts biorubber in a sustainable and environmentally friendly manner utilizing the company’s proprietary water based extraction methods.[6] After harvesting the plant from local growers, it is then delivered to the processing facility for extracting the rubber from the plant. These plant materials are chopped into pieces where the rubber rich stems are separated from the leaves. The stems then are milled in water to release the rubber particles into suspension. The milled stem are then pressed to separate the plant fibers and form a rubber rich liquid, which is then centrifuged concentrating and purifying the liquid into the bio rubber emulsion. [7] After these rubbers are in liquid form it is transported by ship, truck and railroad to the facility to make new products.

Some of the benefits and the features that provide from biorubber emulsion are extended storage and shelf life, a petrochemical –free material, no residual toxic monomers, Hevea-latex-free, no proteins that can trigger Type I latex allergy, extremely low total protein, user defined pervulcanization initiation, exceptional physical performance with unmatched form, fit, feel and function, improved tactile characteristics, custom compounding available and environmentally sustainable and renewable. [8]Biorubbers are suitable for replacing natural rubber as well as petroleum- based synthetics, such as polyisoprene, polychlroprene, nitrile rubber and styrene butadiene rubber. These biorubbers are currently used to manufacture products like footwear, medical equipment, gasketing, chewing gum, tires and auto parts and children toys and gear. Biorubbers also contributes to creating a truly sustainable bio refinery in reducing its carbon footprint. The company is currently pursuing the goal of energy independence for its current and future manufacturing facility, and aims to use biomass it produces to power the plant and go off the grid.

Another material that is used on the wetsuit it neoprene, which is made from limestone rather than petroleum. Limestone is a sedimentary rock created over millions of years from fossilized marine organisms and is remarkably free from impurities.[9] The leading stone produced in the US, limestone accounts for 42% of total domestic production.[10] Limestone, a nonrenewable resource that is mined from the earth with cranes, backhoes and dump trucks the size of houses are crushed and fed into a furnace and heated to extremely high temperatures (over 3,600 F) in an energy-intensive process.[11] The source of the heat used during the process is from burning used tires and hydroelectric power sourced from several local dams. The average gross energy required to produce one ton of limestone is 0.808 million BTUs [12]. From the furnace, components are reacted with other chemicals to make the acetylene gas to form a polychloroprene rubber chips (sponge). These rubber chips are then melted and mixed together with foaming (blowing) agents and pigment, usually carbon black, and baked in an oven to make it expand. The sponge blocks are then processed to slice it up into sheets and its required neoprene thickness. And then, the soft sheets are laminated on one or both sides of fabric with high stretch nylon or polyester jersey knit to give them extra strength and prevention from water leakage.[13] Many of the products that are made from limestone are lightweight, super stretchy, easy to take on and off, 95 percent water impermeable and reduced drag and increased speed. [14]

Recycled Polyester, a product line made from post consumer recycled (PCR) plastic soda bottles or PET as the raw material which are used in the wetsuit to give maximum comfort and freedom of movement in the water. PET, which stands for polyethylene terephthalate is a polymer of ethylene glycol and terephthalic acid that are combined to form polymer chain. There are three steps in the synthesizing of polyester. First, the Condensation Polymerization, where acid and alcohol are reacted in a vacuum at high temperatures resulting in condensation polymerization, after then, the material are extruded onto a casting trough in the form of ribbon, once these ribbons are cooled it is cut into chips. Secondly, it goes through the melt-spun fiber, where each chips are dried completely, heated and extruded through spinnerets and cools upon hitting the air. Lastly, it goes through drawing, where fibers consequently formed are hot stretched to about five times their original length to help reduce the fiber width. This fiber is now ready to be cut into staple lengths as per requirements.[15]

PET can also be recycled through washing and re-melting, or by chemically breaking it down to its component materials to make a new PET. It also has lower energy impacts and can be completely recyclable at the end of its life. According to PET Resin Association, “More than 1.5 billions pounds of used PET bottles and containers are recovered in the United States each year for recycling.”[16] This makes it the most recycled plastic in the U.S and worldwide. Many of the products that are commonly made from recycled PET include, carpet, clothing, industrial strapping, rope, automotive parts, bottles and jars, fiberfill for winter jackets and sleeping bags, construction materials, and protective packaging.[17] PET most of the recycled polyester is being used by Patagonia to satisfy the need of the customers and help to reduce the environmental footprints. Patagonia uses mostly recycle used soda bottles, unusable manufacturing waste, and worn out garments into polyester fibers to produce many of their new clothes. By partnering with Teijin, a Japanese company who developed their own closed –loop polyester recycling system that helps to recycles materials from one product into a similar product as a standard way of recycling. This closed- loop recycling system has helped to reduce energy use by 75 percent and carbon dioxide emissions by 40 percent[18] making it more sustainable environment.

Supra Tex Nylon is a petroleum-based product that is used to create a synthetic fabric. It is highly water-resistant and breathable fiber used in the top layer of jackets, trousers and boots, perfect for all active people who are frequently exposed to hard weather conditions. Nylon is made up of amine, hexamethylen diamin and adipic acid.[19] These chemicals go through a polymerizing process, which was developed by the Wallace Carothers in 1934. In the polymerization process, the first thing the manufacturer combines is two sets of molecules, one with and acid group and one with an amine group which is then heated in a large vat at a very high temperature.[20] The heated molecule is then formed into molten nylon and is transferred to spinneret for separating the nylon into thin threads. As these thin threads are exposed to air it hardens immediately and can be wound onto bobbins and then stretched to create elasticity and strength. Nylon also offers good mechanical and thermal properties. For example, 35 percent of nylon produced is used in the automobile industry.[21] The other percent of nylon is used in textile industry, tubing extrusion, injection molding, and coatings for metal objects. Nylons flexible strength is higher than that of wool, silk, rayon and cotton.[22] It is strong, abrasion resistant, lustrous, easy to wash and resistant to damage from oil and many other chemicals.

Zippers are made of metal, plastic, brass, or nickel. Zippers are used for opening and closing things like pants, skirts, shoes, and garment. These zippers are fitted on wetsuit so the user can easily access without difficulties. Today most of the zippers are manufactured in Japan, a well-known company named YKK Group. The YKK Group is number one leading zippers manufacturer in the world. They make more than 7 billion zippers each year and provides to almost half of the world. They hold 45 percent of the world market share. [23]Zippers come in different types such as, coil, invisible, reverse coil, metallic, plastic-molded, open-ended, and closed- ended and magnetic. Each has its own functions when zipping and unzipping any types of wearable garments. Without the use of zipper the entire garment would be unwearable.

Today, most of the wetsuits that are manufactured by Patagonia are mostly focused in creating products that are eco- friendly and sustainable towards the environment. Many of the products produced by Patagonia are finding ways to improve on their materials that can be easily recycle, reuse and reduces the wastes in the future. Wetsuit is a garment worn by surfers, divers, windsurfers, canoeists, and other water sports activities that provides comfort, warmth and durability to user needs.

Bibliography

{C}1. “An Introduction to PET." Fact Sheet. N.p., n.d. Web. 12 Mar. 2014. <http://www.petresin.org/news_introtoPET.asp>.

{C}2. "From Rocks to Wetsuits - Limestone Based Neoprene..." Celtic Quest Coasteering. N.p., n.d. Web. 09 Mar. 2014. <http://www.celticquestcoasteering.com/from-rocks-to-wetsuits-limestone-based-neoprene/>.

{C}3. "Life-Cycle Studies: Nylon." Worldwatch Institute. N.p., n.d. Web. 13 Mar. 2014. <http://www.worldwatch.org/node/5906>.

{C}4. "How Is Nylon Made?" WiseGEEK. N.p., n.d. Web. 13 Mar. 2014. <http://www.wisegeek.org/how-is-nylon-made.htm#didyouknowout>.

{C}5. "Reference Library." Patagonia. N.p., n.d. Web. 09 Mar. 2014. <http://www.patagonia.com/us/patagonia.go?assetid=68363>.

{C}6. "Materials." Yulex:. N.p., n.d. Web. 08 Mar. 2014. http://www.yulex.com/materials/

{C}7. {C}"Patagonia Men's R1® Back-Zip Full Wetsuit - Tall." Patagonia. N.p., n.d. Web. 10 Feb. 2014. <http://www.patagonia.com/us/product/mens-r1-back-zip-full-tall?p=87311-0>.

{C}8. {C}"Wetsuit History." Buy Wetsuits Online. N.p., n.d. Web. 07 Mar. 2014. <http://www.wetsuitwarehouse.com.au/pages/wetsuit_history>.

{C}9. "Wetsuit Thickness Guide and Temperature Chart." Ski, Snowboard, Wakeboard, Skateboard & the Freshest Clothes. N.p., n.d. Web. 13 Mar. 2014. <http://www.evo.com/wetsuit-thickness-guide-and-temperature-chart.aspx>

{C}10. {C}"Wetsuit History – From Wool Sweaters To Heated Wetsuits." Wetsuits Surfboards Snowboards Videos and Boardblog 360Guide. N.p., n.d. Web. 07 Mar. 2014. <http://360guide.info/wetsuits/wetsuit-history.html#axzz2vKjzJVaM>.

{C}11. {C}"Why Do So Many Zippers Say YKK?" Slate Magazine. N.p., n.d. Web. 13 Mar. 2014. <http://www.slate.com/articles/business/branded/2012/04/ykk_zippers_why_so_many_designers_use_them_.html>

[1] http://www.wetsuitwarehouse.com.au/pages/wetsuit_history

[2] http://360guide.info/wetsuits/wetsuit-history.html#axzz2vKjzJVaM

[3] http://www.yulex.com/about/partners/

[4] http://www.yulex.com/science/crop-science

[5] http://www.yulex.com/science/crop-science/

[6] http://www.yulex.com/science/bioprocessing

[7] http://www.yulex.com/science/bioprocessing/

[8] http://www.yulex.com/science/bioprocessing/

[9] http://www.celticquestcoasteering.com/from-rocks-to-wetsuits-limestone-based-neoprene/

[10]http://www.naturalstonecouncil.org/content/file/LCI%20Reports/Limestone_LCIv1_October2008.pdf

[11] http://www.patagonia.com/us/patagonia.go?assetid=68363

[12]http://www.naturalstonecouncil.org/content/file/LCI%20Reports/Limestone_LCIv1_October2008.pdf

[13] https://www.patagonia.com/pdf/en_US/neoprene_from_limestone.pdf

[14] http://www.celticquestcoasteering.com/from-rocks-to-wetsuits-limestone-based-neoprene/

[15] http://www.whatispolyester.com/manufacturing.html

[16] http://www.petresin.org/news_introtoPET.asp

[17] http://www.petresin.org/news_introtoPET.asp

[18] http://www.patagonia.com/us/footprint/read-the-story/?assetid=68388

[19] http://wanttoknowit.com/where-does-nylon-come-from/

[20] http://wanttoknowit.com/where-does-nylon-come-from/

[21] http://www.engr.utk.edu/mse/Textiles/Nylon%20fibers.htm

[22] http://www.engr.utk.edu/mse/Textiles/Nylon%20fibers.htm

[23] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zipper

Paige Klugherz

DES 40

Research Paper

3/13/14

Energy: Patagonia Yulex R2 Front-Zip Full Wetsuit

Prior to the Industrial Age, when most products were made simply by specialized workers or in the home by users themselves, people were very cognizant of where their goods came from, who made them, and what they were made out of. However, as the world moved into a coal-powered age and products started to become mass-produced in factories, this knowledge was lost to the majority of the population. Thanks to this boom in manufacturing, certain natural resources were over-used to the point of near extinction leading to the creation of man-made synthetic substitutes. While these new substances were crucial to our industrial growth and the continuation of the way of life we are so used to, they can have significant environmental impacts. For this reason, it is becoming increasingly important that we understand what we are actually supporting when we buy a product and how being aware of this can push companies into seeking “greener” alternatives in order to maintain their customer base. Patagonia, a sportswear and outdoor gear company, puts a serious emphasis on producing their products in the least environmentally harmful way possible and being transparent about who produces their goods, how, and where. Through examining the energy used in all aspects of the lifecycle of the Yulex R2 wetsuit, we can see just how thoroughly Patagonia is researching alternative materials and environmentally friendly production processes.

Always at the forefront of innovative, eco-friendly materials, Patagonia has begun using the revolutionary material Yulex for the rubber in their wetsuits. Yulex is made from a plant called guayule grown in the southwestern United States.[i] Because this shrub is native to a desert climate, it requires little water to grow but is receiving a lot of solar energy from the sun and using chemical energy to perform photosynthesis. It is not recorded what type of machinery harvests guayule, but since this is a large-scale commercial crop, we can assume that it is done by some sort of gasoline-powered harvester machine. Next, the shrub is ground up, processed using an aqueous extraction method, and placed in a centrifuge to separate the rubber from the rest of the mixture.[ii] While few details about it are listed, we can assume that they are using kinetic water energy and possibly some sort of fossil fuel powered machine. It is next refined using a mixture of potassium hydroxide and surfactants, compounds that lower the surface tension between two liquids, making use of chemical energy to change the form of the substance.[iii] After this, the solid biorubber is trucked to Port of Oakland in California and then shipped to Patagonia’s wetsuit facility in Thailand, making use of fossil fuels.

Neoprene, one of the most important materials in wetsuits, is usually made from petroleum, however there is another method that uses limestone as its primary raw material.[iv] Limestone is quarried through the use of drills, forklifts, and trucks, all of which make use of fossil fuels, as well as hydraulic splitters, which use waterpower.[v] Next, the limestone is trucked to factories for processing. There, the limestone will be cut using rotary saws powered by electrical energy.[vi] The cut pieces are fed into a furnace using heat generated from burning old tires and hydroelectric power and then mixed with chemicals producing the polychloroprene rubber chips.[vii] They are then melted using thermal energy, mixed with foaming agents and black carbon pigments, and baked in an oven to form a sponge block.[viii] The block is sliced into the desired thickness perhaps using a electricity-powered slicing machine and laminated with polyester jersey.[ix] The final step, of course, is shipping the finished product to Thailand using fossil fuel. There are still issues with this production process because of the chemicals, the high energy required to heat the solution, the fact that limestone is a non-renewable resource, and the fact that the environmental impact has not been fully studied because it’s so new. However, it is commendable that Patagonia is trying to move away from oil dependent goods and look into alternative primary raw materials.

Another material that wetsuits require a lot of is polyester fabric. New polyester is made from petroleum and is considered very environmentally harmful, which is a serious concern because polyester is such a widely used material.[x] Patagonia now works with Teijin, a textile mill in Japan that works toward a goal of a closed-loop recycling system.[xi] This refers to a system that recycles materials from one product into the production of another product, minimizing waste and using materials as many times as possible. In this way, a harmful product like polyester can be produced in a slightly more responsible way. To engage in the garment recycling program, customers mail used clothing to Reno, Nevada and from there, bulk loads are trucked to Oakland Port in California before being shipped across the ocean to Matsuyama, Japan.[xii] According to detailed energy reports, 6337 MJ are used in this transportation process alone for just one bulk shipment.[xiii]

Along with using recycled garments, Patagonia also makes use of recycled polyester, which is created using recycled plastic bottles because both performance sports clothing and plastic bottles are made from polyethylene terephthalate.[xiv] After being sorted, the plastic bottles are washed and ground into small flakes using machine likely powered by electricity.[xv] They are then tossed using kinetic energy, heated using thermal energy, and dried before being melted into a viscous liquid.[xvi] This is an example of chemical processing because the nature of the material is being changed. The liquid is pushed through very small holes to form very thin filaments, which are allowed to harden before being spun together to form a yarn.[xvii] Finally, the polyester yarn is heated through thermal energy one last time to stretch it, and then it is spooled and ready for use.[xviii] Recycled polyethylene terephthalate (PET) uses up to two thirds less energy and 90% less water than the production of new PET and doesn’t need to use any petroleum.[xix] I was unable to find information about the specific machine used in the weaving of Teijin’s fabric, but we can assume they use a type of electric-powered loom like most other large-scale textile producers. After production, the fabric is shipped to Thailand.

SUPRA-TEX nylon, used in the kneepads of the Yulex R2 wetsuit, is an extremely durable fabric that is not only water-resistant, but also breathable along with being able to withstand nearly any weather condition and is highly resistant to tearing.[xx] There is no production information about SUPRA-TEX specially, perhaps because it is such a high tech and relatively new fabric, but there is plenty of information about how general nylon is produced. Nylon is a manmade fabric initially created through chemical processing. The substance is then heated into a molten liquid through thermal energy and then pushed through very small holes in a machine called a spinneret.[xxi] Used when making synthetic fibers, a spinneret looks almost like a showerhead with hundreds of small holes through which thick liquid is extruded and is likely powered by electricity.[xxii] Once exposed to air, the filaments harden and are wound onto bobbins.[xxiii] Finally, the fibers are stretched by being fed around spinning rollers before being wound onto smaller bobbins.[xxiv] The machines that wind and spin the nylon are likely powered by electricity as well, yet this specific information couldn’t be found. The nylon thread is then woven into fabric on large, commercial grade looms before being transported to the Patagonia wetsuit factory in Thailand. The site of the particular factory used for their nylon production is not listed, so I am unsure whether the transportation would require trucking, shipping, or both.

A small but crucial component of the wetsuit is, of course, the zipper. While particulars about the zipper used in the Yulex R2 wetsuit are not listed, since nearly every zipper in the world is manufactured by the Yoshida Manufacturing Corporation (YKK), it’s fairly safe to assume that they are the producer of Patagonia’s zippers as well. Zippers can be made from stainless steel, aluminum, brass, zinc, nickel-silver alloy, or a durable plastic.[xxv] Since wearers want their wetsuits to have as little bulk and weight as possible, the zippers are made out of a durable, heavy duty plastic. The teeth of the zipper are created through a process that makes use of thermal energy to melt the plastic and is then poured into molds.[xxvi] Once the plastic hardens, a machine, likely run by electrical energy, bends the teeth into a U-shape so that they can be sewn onto a strip of polyester.[xxvii]

One of the materials in the wetsuit that is difficult to find information about is the glue used when assembling the wetsuit. Glue is used to join the seams of the pieces of Yulex rubber, neoprene, and more to provide a watertight seal and it’s also used to laminate the recycled polyester to the neoprene.[xxviii] The glue increases the strength of the seam and adds to its flexibility because it allows the thick pieces of fabric to be joined straight together instead of the neoprene being bent back and sewn in order to form a lock that attempts to keep the water out but isn’t very effective.[xxix] It is unclear whether this process is done by human power or by some sort of machine, however I’m guessing that it is done by hand since it requires precision and small detail work.

Finally, Patagonia’s wetsuits are assembled at a factory in Thailand.[xxx] I couldn’t find any information about this particular factory and precisely how the wetsuits are manufactured, however a variety of assumptions can be drawn based on the info we know about the materials and final product. As I’ve stated, the seams are likely glued by hand, but the stitching that adds to the strength of the seams and the addition of the zippers are probably done by machine, but maybe guided by a worker. The lamination is also likely done by machine, but I couldn’t find information about exactly how this process works. After being assembled, the finished wetsuits are shipped from Thailand to the Port of Oakland in California on shipping vessels that run on fossil fuel.[xxxi] From there, they are trucked to their final destinations- Patagonia stores and warehouses across the country from where they will either be directly purchased by a customer or bought online and sent to the customer’s home.

The lifecycle of the Yulex R2 wetsuit does not end there, however. Patagonia is committed to recycling as much of their clothing as possible and will accept customers’ old, used Patagonia clothing.[xxxii] The company is attempting to create a closed loop recycling system and their endeavor is named the Common Threads Garment Recycling Program.[xxxiii] Some of these old garments are sent to factories where they are made into entirely new products, while other garments are sent to Teijin, the recycled polyester factory in Japan that is so focused on being environmentally conscious.[xxxiv] In this process, energy is used to ship the recycled goods to Japan using fossil fuels to power the ships and trucks and energy would also be used in the process of recycling the polyester. Yulex is biodegradable, however it cannot be recycled from the Yulex R2 wetsuit because it is mixed with neoprene. So, it’s apparent that Patagonia is making strides to aid the recycling of their products, but there are still improvements to be made.

While there was often plenty of information about the production process of the materials used in the wetsuit, it was very difficult to find information about the actual machines used in the process. This includes commercial grade looms, harvesters, spinnerets, and more, which meant I was unable to know for certain what the energy source was in certain aspects of the production process. Despite the gaps in information, though, I was still able to learn a tremendous amount about the Yulex R2 Front-Zip Full Wetsuit. It is abundantly clear that sustainability is at the forefront of Patagonia’s mission and that the company is willing to sacrifice some profit in order to assure that their products are being produced in the most environmentally friendly way possible. From conception, to material, to production, to recycling, Patagonia ensures they have researched every aspect of their product, something that is highly admirable in a society where profit and time are often seen as the most valuable things. Through this company, though, we can learn that transparency and a sense of responsibility about what we use is far more important. We as the consumers can support the push towards greener production processes by educating ourselves about where our products come from, how they are produced, and what happens to them once we are finished with them. By trying to only purchase products we believe in and are informed about and also making sure we engage in the recycling programs available to us, we can play a role in the future of production and manufacturing and how it affects our shared environment.

[i] "News." Yulex. Yulex, n.d. Web. 6 Mar. 2014. <http://yulex.com/home/>.

[ii] Ibid.

[iii] Ibid.

[iv] "Green Neoprene?" Patagonia. Patagonia, n.d. Web. 6 Mar. 2014. <http://www.patagonia.com/pdf/en_US/neoprene_from_limestone.pdf>.

[v] "Limestone Based Neoprene." Celtic Quest Coasteering. N.p., 26 Apr. 2013. Web. 6 Mar. 2014. <http://www.celticquestcoasteering.com/from-rocks-to-wetsuits-limestone-based-neoprene/>.

[vi] Ibid.

[vii] Ibid.

[viii] Ibid.

[ix] Ibid.

[x] "Teijin (Wako Ltd.)." Patagonia Footprint Chronicles. Patagonia, n.d. Web. 6 Mar. 2014. <http://www.patagonia.com/us/footprint/read-the-story/?assetid=68388>.

[xi] Ibid.

[xii] Ibid.

[xiii] "Patagonia's Common Threads Garment Recycling Program." Patagonia. Patagonia, n.d. Web. 6 Mar. 2014. <http://www.patagonia.com/pdf/en_US/common_threads_whitepaper.pdf>.

[xiv] "Recycled Polyester." Libolon. N.p., n.d. Web. 6 Mar. 2014. <http://www.libolon.com/recycled-polyester-1.html>.

[xv] Ibid.

[xvi] Ibid.

[xvii] Ibid.

[xviii] Ibid.

[xix] Ibid.

[xx] "Clothing: Supra-Tex." Moosecompany, Bergson. N.p., n.d. Web. 6 Mar. 2014. <http://www.moosecompany.nl/iframe/tech/clothing.htm>.

[xxi] "How Is Nylon Made?" WiseGEEK. N.p., n.d. Web. 6 Mar. 2014. <http://www.wisegeek.org/how-is-nylon-made.htm#didyouknowout>.

[xxii] Ibid.

[xxiii] Ibid.

[xxiv] Ibid.

[xxv] Secrest, Rose. "How Zipper Is Made." Made How. N.p., n.d. Web. 6 Mar. 2014. <http://www.madehow.com/Volume-1/Zipper.html>.

[xxvi] Ibid.

[xxvii] Ibid.

[xxviii] "Wetsuit Stitching." Surfing Waves. N.p., n.d. Web. 6 Mar. 2014. <http://www.surfing-waves.com/equipment/wetsuit-stitching.htm>.

[xxix] Ibid.

[xxx] "The Footprint Chronicles: Our Supply Chain." Patagonia. N.p., n.d. Web. 6 Mar. 2014. <http://www.patagonia.com/us/footprint>.

[xxxi] Ibid.

[xxxii] "The Cleanest Line." The Cleanest Line. Patagonia, n.d. Web. 6 Mar. 2014. <http://www.thecleanestline.com/2009/03/closing-the-loop-a-report-on-patagonias-common-threads-garment-recycling-program.html>.

[xxxiii] Ibid.

[xxxiv] Ibid.

Bibliography

"Clothing: Supra-Tex." Moosecompany, Bergson. N.p., n.d. Web. 6 Mar. 2014. <http://www.moosecompany.nl/iframe/tech/clothing.htm>.

"Green Neoprene?" Patagonia. Patagonia, n.d. Web. 6 Mar. 2014. <http://www.patagonia.com/pdf/en_US/neoprene_from_limestone.pdf>.

"How Is Nylon Made?" WiseGEEK. N.p., n.d. Web. 6 Mar. 2014. <http://www.wisegeek.org/how-is-nylon-made.htm#didyouknowout>.

"Limestone Based Neoprene." Celtic Quest Coasteering. N.p., 26 Apr. 2013. Web. 6 Mar. 2014. <http://www.celticquestcoasteering.com/from-rocks-to-wetsuits-limestone-based-neoprene/>.

"News." Yulex. Yulex, n.d. Web. 6 Mar. 2014. <http://yulex.com/home/>.

"Patagonia's Common Threads Garment Recycling Program." Patagonia. Patagonia, n.d. Web. 6 Mar. 2014. <http://www.patagonia.com/pdf/en_US/common_threads_whitepaper.pdf>.

"Teijin (Wako Ltd.)." Patagonia Footprint Chronicles. Patagonia, n.d. Web. 6 Mar. 2014. <http://www.patagonia.com/us/footprint/read-the-story/?assetid=68388>.

"Recycled Polyester." Libolon. N.p., n.d. Web. 6 Mar. 2014. <http://www.libolon.com/recycled-polyester-1.html>.

Secrest, Rose. "How Zipper Is Made." Made How. N.p., n.d. Web. 6 Mar. 2014. <http://www.madehow.com/Volume-1/Zipper.html>.

"The Cleanest Line." The Cleanest Line. Patagonia, n.d. Web. 6 Mar. 2014. <http://www.thecleanestline.com/2009/03/closing-the-loop-a-report-on-patagonias-common-threads-garment-recycling-program.html>.

"The Footprint Chronicles: Our Supply Chain." Patagonia. N.p., n.d. Web. 6 Mar. 2014. <http://www.patagonia.com/us/footprint>.

"Wetsuit Stitching." Surfing Waves. N.p., n.d. Web. 6 Mar. 2014. <http://www.surfing-waves.com/equipment/wetsuit-stitching.htm>.

Cody Whittle

DES 040A

March 13th, 2014.

Patagonia’s Yulex R2 Wetsuit - Wastes and Emissions

We, as humans, are fortunate enough to live on a beautiful little blue planet somewhere within a galaxy amongst others that make up our vast solar system. Every bit of this being the organic lifecycle of nature and its elements therein; however, we are also lucky in that we have the ability to change our natural surroundings in such a way that best suits our needs, or in most cases, our desires. Our model for success since the discovery of agriculture has been how well we can harness our natural resources to make our lives easier; this model, since the beginning of the industrial revolution, and more specifically, since the discovery of fossil fuels, has become how well can we process these natural resources into products that make our lives more productive, or fun, or gratifying? We have answered this question for ourselves by using fossil fuels to both sustain our energy needs and to use in our production of synthetic materials for consumer goods and fossil fuel driven services. In this “growth” we have lost site of just where these materials and products come from and, more negatively, what impact they may be having on the natural cycle of our little blue planet.

Our group chose to do a life cycle analysis on the Yulex R2 Wetsuit, a product of Patagonia Inc., because we wanted to show a product that includes the petroleum based synthetic materials that we have been using for some time, as well as examples of a new conscious movement towards more environmentally respectful materials and business models that provide a link between efforts to take care of our natural environment and still being able to enjoy the products we have come to expect. Throughout this paper I intend to report the information that I have found regarding produced and emitted waste as byproducts of the manufacturing process and life of the Yulex R2 Wetsuit. First by examining materials used and the waste created through their development, and then by examining the production, distribution, lifespan of product, and final product end of life outcome. With this examination I hope to set out a clear map of the waste created through the entire life cycle of the Yulex R2 Wetsuit.

Yulex

The first material I will cover is the most exciting material used in the Yulex R2 wetsuit, and the primary reason that we chose this product to report on earning its place in the name of the wetsuit for its importance, Yulex. Yulex is a newly developed bio-rubber created from a desert shrub called Guayule that is native to the American Southwest1. The guayule plant has evolved to depend very little on water and creates its own terpene resins, which act as natural insect deterrent and pesticide2; additionally, it is a perennial crop that can be harvested every year and only has to be replanted every five years3. Extraction of the rubber is done through aqueous milling where the chopped up plant material is agitated in water until the rubber molecules are released and float to the top to be skimmed off and ran through a centrifuge to further process the base material; there is no pollution of the water as it is solely plant based materials and Yulex does not require the harsh compounds and chemical solvents other forms of rubber require which release harmful VOCs (volatile organic compounds) into the atmosphere4. Further processing turns the bio rubber into usable chips for different types of manufacturing needs, which are then mixed into a 60/40 blend of Yulex/Neoprene for the Yulex R2 Wetsuit creating a wetsuit that is 60% biodegradable5. Because of its low requirements as a crop and its proximity to the processing sites, Yulex bio rubber extraction is a nearly closed loop system that creates little to no waste in its methods. Primary waste would be that of fossil fuel emissions from agricultural harvesting machinery, and the electrical needs of the processing facility; however, spent guayule plant material is being used to power part of this process as it is an ideal bio fuel for outright burning as biomass, or development into a gas to be used more widely. Yulex biomass currently powers two energy-generating plants in Arizona6.

Polyester

Patagonia uses both virgin and recycled polyester in the interior liner of the R2 wetsuit, as well as the exterior lamination of the sponge (the Yulex/Neoprene rubber foam that makes up the majority of the wetsuit), where virgin polyester is blended with recycled polyester for added durability, as well as the stitching used for the seams of the suit.

Virgin polyester is a synthetic material derived from coal, air, water, and petroleum by which secondary chemicals form a reaction between an acid and an alcohol and, through polymerization, fibers can be formed and woven into a textile material7. The main contributor to waste in the production of virgin polyester is fossil fuel emissions. Fossil fuels are not only the primary materials needed to produce polyester but also the materials used to create the secondary energy needed for the mineral extraction and the electrically intensive manufacturing process; this process requires approximately 18.3 Kwh per pound of fiber8. Manufacturing of virgin polyester releases CO2, VOCs, particulate matter, and acid gases such as hydrogen chloride9 into the atmosphere. Though energy use is high for the production of virgin polyester, there is very little material waste, and the only water used is for cooling purposes and should not result in water pollution.

Comparatively, recycled polyester is a much better environmental option as it uses recycled plastic bottles and worn out polyester to produce new polyester fabric by one of two ways. The first and most common form of polyester recycling is through mechanical means where the plastic and polyester is melted down and re-extruded into new polyester yarn; this process is limited in its efficiency due to the fact that every time the plastic or polyester is recycled mechanically it loses quality and strength, which means that eventually the material would end up being thrown out10. The other type of recycling polyester is chemically; in this process the polyester is broken down to its molecular parts and restructured into new yarn and can be done indefinitely11. This method, however, is unfortunately too expensive to currently be the popular choice of the two options. Recycling polyester uses up to 53% less energy and releases approximately 55% less CO2 emissions than creating virgin polyester, but releases antimony trioxide, a harmful carcinogen, when melting the plastic or polyester12.

Supratex

Supratex is a nylon material used on the knees of the wetsuit for added durability in high stress parts of the suit. Nylon is also a synthetic material derived from petrochemicals, in much the same way as polyester, but with a more rigid and durable final structure. As with polyester, the majority of waste produced through the production of Nylon is due to fossil fuel emissions from mineral extraction and processing. Nylon, however, is more difficult to recycle than polyester resulting in more material waste, and the chemical production of adipic acid needed for Nylon production frequently creates nitrous oxide, a known greenhouse gas13. Water, like polyester, is only used for cooling and should not result in chemical pollution14.

Neoprene

Neoprene, a material mixed with Yulex to form the majority of the R2 wetsuit’s foam structure, is also a synthetic material generally made from petrochemicals. The Neoprene used by Patagonia for their wetsuits is not, however, petroleum based but made from limestone, a mineral created by the calcium deposits of ancient ocean dwelling organisms. The manufacturing of neoprene is a waste intensive process as the limestone must first be extracted from quarries using heavy machinery releasing CO2 into the atmosphere, and then the limestone must be crushed and fed into a furnace and heated to extremely high temperatures (over 3,600°f)15 obviously lending itself to the idea that more fossil fuels are needed to produce such heat. Patagonia admits that neoprene made from limestone, in the big picture, is not any better for the environment than petroleum based neoprene, but has the benefits of lacking reliance placed upon oil for production and the risk of future oil spills16.

Zippers

Though little could be found on the exact materials used in the production of the zippers used for R2 wetsuits, we do know that the teeth and hardware of the zipper are that of a hard plastic while the fabric along the sides of the hardware is made of Nylon; that being said, we can assume that the same waste created by the production of the Supratex Nylon knee pads could be carried over into the materials of the zipper. Additionally, the YKK factory where the zippers are manufactured operate large amounts of mechanical equipment necessary for precision manufacturing of zippers, and because of this, require lots of fossil fuel based energy allowing for more CO2 emissions to be emitted.

Glue

There was also very little information found on the exact material ingredients used in the contact adhesive needed to seal the wetsuits, but it can be safely inferred that fossil fuel based CO2 emissions were released as a result of petroleum extraction and refinement. Solvents from the production and use of these glues release VOCs and other toxins into the air; it is estimated that nearly 800 tons of solvents evaporate into the atmosphere because of current wetsuit gluing and neoprene laminating processes17. Non solvent based eco glues are being developed but when asked why they were not being used by the company yet, a Patagonia representative stated, “At this point, unfortunately, current non solvent based glues do not hold up to the high quality expectations Patagonia has for its products.”18

Shipping, Manufacturing, and Lifespan

Transportation of materials and products is one of the leading waste producers for Patagonia as nearly all products are outsourced to manufacturers around the world. Over 60% of clothing and gear is made in Asia, and the wetsuits themselves are manufactured in Thailand and shipped to the Port of Oakland where they are trucked to Patagonia’s distribution center in Reno, Nevada19. It is hard to calculate just how much CO2 emissions are released due to wetsuit shipping alone, but an estimate can be made based on an article found regarding Patagonia’s shipping practices. This article stated that since Patagonia switched from the Port of Los Angeles/Long Beach to the Port of Oakland in 2011, because trucking releases 4-7 times more carbon emissions than shipping, and they no longer had to truck goods up from L.A. to Reno, the company was able to reduce its carbon footprint by 31% or 135,000 kilos20. I am not aware if this total carbon footprint includes shipping to customers through catalog or online purchases but I would assume that it does cover shipments to retailer locations.

Manufacturing of the actual wetsuits in Thailand accounts for some of the lowest percentages of waste because energy use is low with a mostly hand made product and little material waste, though the energy needed to produce work environments that hold up to high standards of workers safety and comfort could be considered.

Once a Yulex R2 Wetsuit makes it to a customer there is very little maintenance necessary for the life of the suit, it must merely be rinsed off to prevent corrosion from salt water, and if there are issues with the quality, or the suit’s structure is compromised, Patagonia will fix it so that you don’t buy another one.

Recycling

Finally, when the wetsuit reaches the end of its working life and is no longer capable of keeping water lovers warm in the water there are a few options of where it may go. It could get put in the trash and in which case end up in the landfill, it could get left on the beach to break down though only the Yulex is truly biodegradable, it could be incinerated releasing harmful chemicals into the air, or it could get sent back to Patagonia through direct shipment or retail store drop off to be recycled or reused by the company. Another primary reason for choosing to focus on a product made by Patagonia is to shed light on its program of recycling products called the Common Threads Partnership. Since 2005 Patagonia has partnered up with a few textile-recycling mills in Asia, primarily Japanese based company TEIJIN, to accept all Patagonia products for either reusing to make other goods or recycled to create new fabrics21. In the near future Patagonia hopes to make all products recyclable and since 2007 has even started accepting recyclable fabrics from a few other companies who compete with Patagonia. Patagonia sources say about the decision to recycle their materials, “We found that making DMT (dimethyl terephthalate, the precursor material to polyester in TEIJIN’s process) from Patagonia polyester uses 76% less energy and emits 42% less CO2 than making it from petroleum. The CO2 savings jumps to 77% if the garment is incinerated instead of recycled.”22

Through my research efforts for this product lifecycle project I have become increasingly aware of the unseen processes that every product must go through, its hidden effects on the environment, and lack of the transparency that would lead to stronger consumer knowledge of the products and materials that they are buying. I feel that it is important for company information be made clear to all in order to develop a safer market for public and environmental health. Though I have respected Patagonia’s business ethics for quite some time now because of their desire to do better through programs like the Common Thread Partnership, 1% for the Planet, environmental activism, and their partnership with Bluesign Technologies (a private Swiss company that helps Patagonia monitor the human and environmental safety of materials that they use), I tried to take an objectionable approach and dig into as much dirt as I could find on the manufacturing process of a product. I found Patagonia itself to be the most openly transparent source for research material, honestly providing information on materials and their uses, and enthusiastically pointing out its own flaws in hope for development of better materials to work with. In the end, I feel that it is just as important for consumers to make good, conscious, decisions about the products they buy and their effects on the world around them as it is for companies to make information known to consumers and begin to live by Patagonia’s mission statement of, “Build the best product, cause no unnecessary harm, [and] use business to inspire and implement solutions to the environmental crisis.”23 This has been an excellent exercise in the kind of examination we all should be doing as consumers and respectful citizens of this little blue planet.

Sources Cited:

1) "Patagonia Yulex Wetsuits - From Seed To Suit." YouTube. YouTube, 31 July 2013. Web. 13 Mar. 2014.

2) "Patagonia Yulex Wetsuits - From Seed To Suit." YouTube. YouTube, 31 July 2013. Web. 13 Mar. 2014.

3) "Patagonia Yulex Wetsuits - From Seed To Suit." YouTube. YouTube, 31 July 2013. Web. 13 Mar. 2014.

4) "Science." Yulex: / Crop. N.p., n.d. Web. 13 Mar. 2014. <http://www.yulex.com/science/crop-science/>.

5) "Science." Yulex: / Bioprocessing. N.p., n.d. Web. 13 Mar. 2014. <http://www.yulex.com/science/bioprocessing/>.

6) "Science." Yulex: / Materials. N.p., n.d. Web. 13 Mar. 2014.

<http://www.yulex.com/science/materials-science/>.

7) "How Products Are Made." How Polyester Is Made. N.p., n.d. Web. 13 Mar. 2014. <http://www.madehow.com/Volume-2/Polyester.html#b>.

8) Baugh, Gail. "Social Responsibility." Social Responsibility. N.p., n.d. Web. 13 Mar. 2014. <http://www.udel.edu/fiber/issue2/responsibility/>.

9) "Polyester Manufacture." Polyester Manufacture. N.p., n.d. Web. 13 Mar. 2014. <http://www.unearthme.com/story111005.html>.

10) "O ECOTEXTILES." O ECOTEXTILES. N.p., n.d. Web. 13 Mar. 2014. <http://oecotextiles.wordpress.com/2009/07/14/why-is-recycled-polyester-considered-a-sustainable-textile/>.

11) "O ECOTEXTILES." O ECOTEXTILES. N.p., n.d. Web. 13 Mar. 2014. <http://oecotextiles.wordpress.com/2009/07/14/why-is-recycled-polyester-considered-a-sustainable-textile/>.

12) "O ECOTEXTILES." O ECOTEXTILES. N.p., n.d. Web. 13 Mar. 2014. <http://oecotextiles.wordpress.com/2009/07/14/why-is-recycled-polyester-considered-a-sustainable-textile/>.

13) "How Is Nylon Made?" WiseGEEK. N.p., n.d. Web. 13 Mar. 2014. <http://www.wisegeek.org/how-is-nylon-made.htm>.

14) "How Is Nylon Made?" WiseGEEK. N.p., n.d. Web. 13 Mar. 2014. <http://www.wisegeek.org/how-is-nylon-made.htm>.

15) "Reference Library." Patagonia. N.p., n.d. Web. 13 Mar. 2014. <http://www.patagonia.com/us/patagonia.go?assetid=68363>.

16) "Reference Library." Patagonia. N.p., n.d. Web. 13 Mar. 2014. <http://www.patagonia.com/us/patagonia.go?assetid=68363>.

17) "Reference Library." Patagonia. N.p., n.d. Web. 13 Mar. 2014. <http://www.patagonia.com/us/patagonia.go?assetid=68363>.

18) "Patagonia Customer Service Questions." Telephone interview. 10 Mar. 2014.

19) "Changing Ports Pays Dividends." Changing Ports Pays Dividends. N.p., n.d. Web. 13 Mar. 2014. <http://www.patagonia.com/us/patagonia.go?assetid=79365>.

20) "Changing Ports Pays Dividends." Changing Ports Pays Dividends. N.p., n.d. Web. 13 Mar. 2014. <http://www.patagonia.com/us/patagonia.go?assetid=79365>.

21) "Closing the Loop - A Report on Patagonia's Common Threads Garment Recycling Program." The Cleanest Line. N.p., n.d. Web. 13 Mar. 2014. <http://www.thecleanestline.com/2009/03/closing-the-loop-a-report-on-patagonias-common-threads-garment-recycling-program.html>.

22) "Closing the Loop - A Report on Patagonia's Common Threads Garment Recycling Program." The Cleanest Line. N.p., n.d. Web. 13 Mar. 2014. <http://www.thecleanestline.com/2009/03/closing-the-loop-a-report-on-patagonias-common-threads-garment-recycling-program.html>.

23) "Closing the Loop - A Report on Patagonia's Common Threads Garment Recycling Program." The Cleanest Line. N.p., n.d. Web. 13 Mar. 2014. <http://www.thecleanestline.com/2009/03/closing-the-loop-a-report-on-patagonias-common-threads-garment-recycling-program.html>.

Bibliography

Baugh, Gail. "Social Responsibility." Social Responsibility. N.p., n.d. Web. 13 Mar. 2014. <http://www.udel.edu/fiber/issue2/responsibility/>.

"Changing Ports Pays Dividends." Changing Ports Pays Dividends. N.p., n.d. Web. 13 Mar. 2014. <http://www.patagonia.com/us/patagonia.go?assetid=79365>.

"Closing the Loop - A Report on Patagonia's Common Threads Garment Recycling Program." The Cleanest Line. N.p., n.d. Web. 13 Mar. 2014. <http://www.thecleanestline.com/2009/03/closing-the-loop-a-report-on-patagonias-common-threads-garment-recycling-program.html>.

"How Is Nylon Made?" WiseGEEK. N.p., n.d. Web. 13 Mar. 2014. <http://www.wisegeek.org/how-is-nylon-made.htm>.

"How Products Are Made." How Polyester Is Made. N.p., n.d. Web. 13 Mar. 2014. <http://www.madehow.com/Volume-2/Polyester.html#b>.

"O ECOTEXTILES." O ECOTEXTILES. N.p., n.d. Web. 13 Mar. 2014. <http://oecotextiles.wordpress.com/2009/07/14/why-is-recycled-polyester-considered-a-sustainable-textile/>.

"Patagonia Customer Service Questions." Telephone interview. 10 Mar. 2014.

"Patagonia Yulex Wetsuits - From Seed To Suit." YouTube. YouTube, 31 July 2013. Web. 13 Mar. 2014.

"Polyester Manufacture." Polyester Manufacture. N.p., n.d. Web. 13 Mar. 2014. <http://www.unearthme.com/story111005.html>.

"Reference Library." Patagonia. N.p., n.d. Web. 13 Mar. 2014. <http://www.patagonia.com/us/patagonia.go?assetid=68363>.

"Science." Yulex: / Bioprocessing. N.p., n.d. Web. 13 Mar. 2014. <http://www.yulex.com/science/bioprocessing/>.

"Science." Yulex: / Crop. N.p., n.d. Web. 13 Mar. 2014. <http://www.yulex.com/science/crop-science/>.

"Science." Yulex: / Materials. N.p., n.d. Web. 13 Mar. 2014.

<http://www.yulex.com/science/materials-science/>