Design Life-Cycle

assess.design.(don't)consume

Poster Image Source: Hliznitsova, Kateryna. “Photo by Kateryna Hliznitsova on Unsplash.” Beautiful Free Images & Pictures, 19 Oct. 2021, https://unsplash.com/photos/2NDtPNiLcD0.

Jemima Jagger-Wells

Professor Christina Cogdell

DES 40 WQ23

17 March 2023

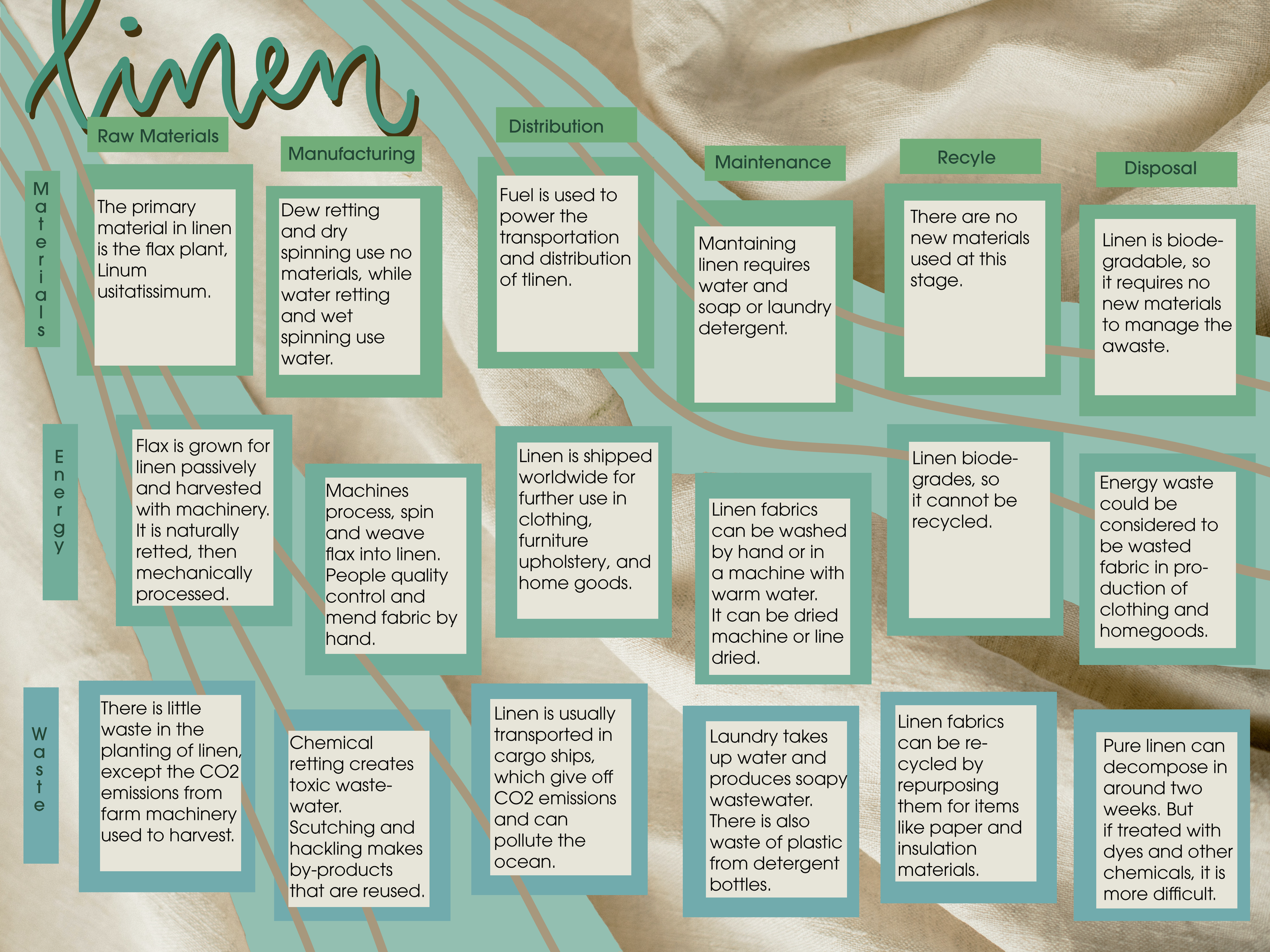

Materials in the Linen Lifecyle

Linen is one of the most common and oldest fabrics in the world. Since the Middle Ages,

it has been used for everything from clothing to upholstery. Making linen is a laborious,

muli-step process, from growing the flax to processing the fibers to spinning the yarn and

weaving the fabric. Although the methods involved in this process have changed significantly

over time—from human to machine labor, from natural to chemical treatments—the materials

necessary for making linen have stayed consistently low. The primary material used in linen is

the flax plant. Some manufacturing methods use water, others use chemicals, and maintaining

the finished fabric requires soap and water. Because it takes so few resources to produce, and

many of them are natural, linen is environmentally friendly.

The primary material in linen is the flax plant, Linum usitatissimum. This clasifies linen

as a plant fiber, as opposed to a animal fiber such as wool, or a synthetic fiber. Like other

common plant-based textiles such as jute, hemp and ramie, linen is a bast fiber, meaning the

fibers are collected from the inner bark surrounding the stem of the plant. Flax fibers vary in

length from one to six inches, with a diameter to of 15 to 22 micrometers. This is longer than

cotton fibers but thinner than jute or hemp, resulting in yarn that is both fine and strong. Flax is

grown in temperate climates, most often in Europe. The flax plant grows in long, grassy stalks up

to three feet tall with blue flowers. It is an annual plant, meaning it only lives for one season and

requires replanting every year. Flax is planted in April and grows for three months, when the

plants begin to wither. To harvest, the plants are pulled up by the roots rather than cut, to

preserve the length of the fibers.

The next step in the manufacturing process is called retting, a process by wich the pectin

that blinds the fibers to the wooden interior is broken down. Retting requires different materials

depending on the method used. The first is dew retting, when the flax stems are spread on a field

and left, allowing the bindings to decompose naturally. This can take from two to twelve weeks,

depending on the climate. Water retting is a process by which the flax is sumberged in water

until the binding is broken down. In warm water, this takes only three or four days. Finally, there

is chemical retting where the flax is treated with chemicals in a process that takes less than a day.

Although chemical retting is fastest, it is expensive, harmful to the environment and lowers the

quality of the fiber. Water retting produces the highest quality fiber, but it also costly and

detrimental to the environment both due to pollution and high water usage. Modern processes

have reduced water usage by allowing the water to be reused indefinitely. That said, dew retting

is by far the least costly, in terms of both money and materials, requiring only time, space, and

air. Water retting is used for finer linen products, but dew retting is far more common in modern

linen production.

Next is breaking and scutching, which require no materials other than machinery. Once

the retted flax is fully dry, it is put through a series of mechanical rollers that crush the now

rotted wood at the center. Then the flax is beaten, or scutched, to further separate the fibers from

the now broken wood. Scutching used to require people to laboriously beat the flax by hand,

until the process switched to machines in the early 20th century. Next is hackling, when the

fibers are combed to remove the remaining debris, separate the long fiber—or the line

fiber—from the short—or tow—fiber.

At this point the fibers are ready to be spun and woven, processes that again require

different materials for different methods. Dry spinning is the simplest method of spinning flax,

requiring no additional materials and limited energy. Wet spinning, however, uses warm water.

Additionally, some wet spun flax is treated with chemicals to create a soften them. As a result of

the more intensive treatment, wet spinning is capable of creating a finer, more high quality yarn.

Yarn created by dry spinning is more rough, but it is still the more common method as it uses

fewer materials and less energy, and is therefore less expensive. Next, the yarn is woven on

mechanical looms. During this step in the process, starch is often used as a glueing and stiffening

agent.

After weaving, linen is usually bleached and dyed. Without bleaching, linen varies

greatly in color depending on the variety of the flax plant and the retting process. To eliminate

this variation, most commercially used linen is bleached. The process of bleaching is precise and

difficult, as it necessitates removing impurities while damaging the fibers as little as possible.

Chemical bleaching agents are used, although the specifics vary depending on the end use of the

fabric. If the linen is to be dyed, chemical dyes are used, as well as chemical agents that help to

fasten the dye to the fabric. Both bleachin and dying are multi-step processes requiring a number

of chemical components, making them the most material intensive steps in the manufacturing

process.

Although it does not directly contribute to the linen itself, it is important not to overlook

the materials necessary for the transportation of linen during manufacturing. Namely, the fuel

used to power cargo ships. Flax is most commonly grown in Eurpean countries with relatively

temperate climates, such as France, Belgium, the Netherlands and Italy. Once it is grown, retted

and scutched, flax is usually shipped to China to be spun, woven and dyed. Then, the finished

fabric is shipped all over the world for sale and distribution. One study found that transporting

980 kg of flax to be spun was 19,110 tkm (ton-kilometers), and transporting the same yarn to be

woven was another 16,380 tkm. Such a distance requires the use of a lot of fuel.

Linen is an incredibly durable material and can last a very long time requiring only

washing. Linen product can last entire lifetime, or even be passed between generations. To be

maintained, the fabric must be washed with water and soap or laundry detergent. If washed

regularly for years, this is not insignificant. However, the soap and water used to maintain linens

is significantly less than the materials required to manufacture new ones. Thus, the longevity of

linens results in fewer materials used overal.

The disposal of linens does not require any additional materials. Linen is a natural fiber,

meaning it is biodegradable and will decompose naturally. Undyed linen decomposes very

quickly, in some cases as quickly as two weeks, while bleached or dyed linen can take much

longer.

From beginning to end, the lifecyle of linen requires very few materials. Beyond flax

itself, the manufacturing process makes use of water, starch and some chemicals. Many parts of

the process have alternative methods that use no resources at all. The most harmful materials

used are the chemicals necessary to bleach and dye the fabrics, as well as the fuel used to

transport and the flax and distribute the linen. However, the environmental cost of this is offset

somewhat by the fact that linen can last for years without needing replacement, and decomposes

naturally. Overall, the low material cost makes linen and environmentally friendly fabric.

Works Cited

Akin, Danny E. “Linen most useful: perspectives on structure, chemistry, and enzymes for

retting flax.” ISRN biotechnology vol. 2013 186534. 30 Dec. 2012,

doi:10.5402/2013/186534

Gębarowski, Tomasz, et al. “Investigation of the Properties of Linen Fibers and Dressings.”

International Journal of Molecular Sciences, vol. 23, no. 18, 2022, p. 10480.,

doi.org/10.3390/ijms231810480.

Gomez-Campos, Alejandra, et al. “Flax Fiber for Technical Textile: A Life Cycle

Inventory.” Journal of Cleaner Production, vol. 281, 2021, p. 125177.,

doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.125177.

Hakoo, Ashok. “Characteristics of Flax/Linen Fiber.” Textile School, 5 May 2019,

https://www.textileschool.com/2632/linen-fiber-from-flax-plants-and-the-linen-fabrics/.

Hann, M. A. “Innovation in Linen Manufacture.” Textile Progress, vol. 37, no. 3, 2005, pp.

1–42., doi.org/10.1533/tepr.2005.0003.

“Is Linen a Sustainable Fabric?” Linenbeauty, 20 June 2021,

https://www.linenbeauty.com/blog/is-linen-a-sustainable-fabric#:~:text=Linen%20is%20on

e%20of%20the%20most%20sustainable%20fabrics%20you%20can,synthetic%20additions

%2C%20pesticides%20and%20chemicals.

Radchenko, Olga, et al. “Development of Options for the Implementation of the

Technology of Manufacturing Linen Products, Combined with the Softening of

Semi-Finished Products.” INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON TEXTILE AND

APPAREL INNOVATION (ICTAI 2021), 2022, doi.org/10.1063/5.0077242.

Ryszard M., Kozlowski, et al. “Future of Natural Fibers, Their Coexistence and

Competition with Man-Made Fibers in 21st Century.” Molecular Crystals and Liquid

Crystals, vol. 556, no. 1, 2012, pp. 200–222., doi.org/10.1080/15421406.2011.635962.

Sutton, S.C. “Background History of Linen from the Flax in the Field to Finished Linen

Cloth.” Background History of Linen,

https://web.archive.org/web/20210512024057/http://www.craigavonhistoricalsociety.org.u

k/rev/luttonhistoryoflinen.html.

Vasta, et al. “Place-Based Policies for Sustainability and Rural Development: The Case of a

Portuguese Village ‘Spun’ in Traditional Linen.” Social Sciences, vol. 8, no. 10, 2019, p.

289., https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci8100289.

Sofi Zurek

Nithya Duggaraju, Jemima Jagger-Wells

Des 40A / Section A02

Professor Cogdale

Embodied Energy in the Life of Flax to Linen

In the consciousness of the modern consumer faced with the hunt for sustainable materials, linen is making yet another comeback. Linen has been a popular fabric for millennia and is made straight from flax. The energy required to grow flax is low, processing the fiber is notably arduous. It must be noted that spinning this flax fibers into yarn requires an intense amount of energy. Despite this, linen has strength, breathability, and cooling properties which are difficult to match with synthetics. Not to mention it is incredibly efficient to maintain and — when finally worn out — breakdown this material. Linen is an environmentally friendly, high-quality natural fabric which requires a reasonable amount of energy to make, maintain, and decay.

Flax is a beloved cover crop in temperate climates, and therefore it is no surprise it is an effortless, passive plant to cultivate in the right environment. Native to Northern Europe, flax is very sensitive to its environment, to the point where different countries cultivate different strains to suit the slightly varied climates (Dimmock, et al., p. 301). It grows with little effort in countries like Canada and China as well, as they have similar climates. Irrigation is not necessary in this case (Turner, 1987) Until the flax is ready to be harvested in early summer, the only energy it needs is that of the sun and natural elements such as snow, rain, and dew. It is more energy efficient if flax is farmed without using chemical fertilizers and pesticides. The creation and use of chemical pesticides actually uses an immense amount of energy. If a flax farm uses these agrochemical materials to grow their crop, this would actually be the most energy consuming step of the whole lifecycle at 49% (Dissanayake, p. 340).

The flax is matured once the field starts to bloom in white and blue, each stock flowering only for one day. The whole plant must be pulled up from the roots using special farm equipment which of course use fossil fuels to run for their season. This is not the only piece of heavy machinery used in the process of harvesting flax for linen fiber production. Specialized farm equipment is also used to turn the swaths so they can evenly ferment and break down in the sun and dew. This process is known as “retting”, specifically dew retting. Dew retting uses very low energy consumption as opposed to chemical or water retting because chemicals and water don’t need to be distributed at all. This saves energy in the manufacture of chemicals, the transportation, the machinery and labor needed to perform these treatments. These practices are commonly used nonetheless, but dew retting is completely passive and relatively quick (5-7 weeks)(Hahn, et al. p. 8). After retting is complete, another diesel or gasoline-powered tractor is used to roll the retted swaths into bales. This is the modern day process for harvesting flax and getting it prepared to be transported to a mill to become linen.

The bales of dried flax are transported by big rigs, typically to mills that are established in the same domestic region that the flax is grown. Processing and especially spinning is the stage which uses the most embodied energy out of the entire linen lifecycle (Dissanayake, p. 331). Mills run off various forms of electricity including coal, electricity, hydropower, and fuels.. Scutching is the first key step in processing linen fibers, and involves breaking up woody tissue in order to start to make the linen fibers soft and malleable. Since 1920, scutching has been done via scutching machine, which uses turbine blades to break and beat the linen fibers and is 3-5 times faster than scutching manually (Hahn, 11). The next mechanical process is hackling, which is done by a machine run combing apparatus to further remove woody tissue. After the fibers have been separated and spread into a continuous sliver of fibers ready to be spun, all via machine called a spreadboard, which uses gravity and leather belts to lay pieces of flax with a tight overlap (Lutton, 2009).

There are two main methods of spinning flax — dry spinning and wet spinning. Wet spinning requires the use of warm water, which means it is the less energy efficient method. Wet spinning uses complex machinery, warm water troughs, and hot air driers to process the more high quality fibers into a tight, strong yarn (Hahn, p. 17-19). Spinning alone uses 4414 KWh of electricity, 24024 MJ of gasoline, and 12.74 m^2 of water (all to become wastewater) per 910 kg of linen yarn (Gomez-Campos, et al., pg.4). The use of such a massive amount of fossil fuels and water is what really puts spinning at a high energy consumption being that they are unrenewable sources of energy. Weaving uses still more electricity than the spinning process at 11830 KWh per 840kg of textile. Of course, not every mill has the same operation. For example, France and China use different sources of energy. In a study done by Ecoinvent v3.4 processes, France uses primarily wind (84%) and solar power (44%) to run their mills whereas China uses coal (77%) and hydropower (20%) (Gomez-Campos, et al., p. 7) This is only one comparison, too. With linen being produced in more than a dozen countries producing this textile in North America, Europe, the UK, and Asia there is certainly room for variation of energy sources.

Dyeing and bleaching is another chemical process — chemicals often being a very energy intensive substance to make and utilize. Dyes use massive amounts of heated water, special earth pigments and synthetic dyes, fixatives, heavy machinery for mercerization (Hahn, p. 27). A more sustainable and energy efficient option is using local natural dyes, oak galls for example, which can be done on a small scale using accessible, unique, eco-friendly pigments. Linen is known to be stubborn when it comes to taking dyes, so it makes sense that it can take extra energy to achieve a perfect dye color. One method used by Ibrahim et al. in 2010 used microwaves to fix dyes without the addition of salts and synthetic mordants, producing a more energy efficient result (Ibrahim, et al., pg. 126). There are alternatives to minimize energy usage in the dyeing and bleaching of linen fabrics, that can yield lasting results.

With the production of the actual textile complete, linen fabric moves on to clothing and home furnishing production before eventually moving on to the marketplace. Linen is a popular fabric especially in warm climates, which means it has distribution worldwide. With production in Canada, China, and Europe linen is shipped via cargo ships and freight trains which run off an intense amount of coal and fossil fuels. Of course, this goes for every exports product in the modern world so it is not out of the ordinary. As far as fabric exports go, linen does not have any specific energy needs that are out of the ordinary.

Once linen goods are in the hands of the consumer, they can last at least a lifetime with moderate maintenance. This is key in linen’s value as a sustainable textile. Linen not only gets softer with wear, it is strong and easy to maintain. It is the consumer’s responsibility to care for their linen, because when well maintained linen clothing and home goods can be passed down trough generations, minimizing the amount of times this process has to be repeated. The usage of laundry machines must be recognized as a source of embodied energy in the linen lifecycle. The efficiency of laundry machines has increased since the 1980’s, with the energy consumption lowering from 268 kWh to 166 kWh (Yates et al., p. 102). Energy can be conserved further by washing linen with cold water, which will also result in a longer life for the textile. Furthermore, energy can be saved and the articles’ life can be increased by lowering the frequency of washes and line drying.

Mending and upcycling linen cloth prolongs its life and helps minimize energy. This is done in a small, close loop for the most part and does not add much more energy,. Likewise, once the textile is truly spent, linen can break down easily via decomposition as long as it’s not treated with heavy chemicals. The end of linen’s lifecycle is graceful in that after it is in the consumers’ hands, the only significant energy required is in laundering.

Linen is a natural textile which has great benefits for the user being that it is long lasting and easy to maintain. Most of linen’s embodied energy is in the transformation from retted flax into spun linen cloth. Linen’s recommended care is infrequent cold water washes and line drying or tumbe dry low, which is low energy care compared to other manmade textiles. Another benefit to the consumer is linen’s longevity and beautiful finish. It is a fiber that gets better and softer with age and can last a lifetime.

Bibliography

Dimmock, J. P. R. E., et al. “Agronomic Evaluation and Performance of Flax Varieties for Industrial Fibre Production.” The Journal of Agricultural Science, 2005/09/30 ed., vol. 143, no. 4, 2005, pp. 299–309. Cambridge Core, Cambridge University Press, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021859605005277.

Dissanayake, Nilmini P. J., et al. “Energy Use in the Production of Flax Fiber for the Reinforcement of Composites.” Journal of Natural Fibers, vol. 6, no. 4, Nov. 2009, pp. 331–46, https://doi.org/10.1080/15440470903345784.

Gomez-Campos, Alejandra, et al. “Flax Fiber for Technical Textile: A Life Cycle Inventory.” Journal of Cleaner Production, vol. 281, Jan. 2021, p. 125177. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.125177.

Green, Jennifer. “Spin Me Some Flax.” Journal of Textile Design Research and Practice, vol. 2, no. 2, Nov. 2014, pp. 187–99, https://doi.org/10.2752/205117814X14228978833538.

Hann, M. A. “Innovation in Linen Manufacture.” Textile Progress, vol. 37, no. 3, Aug. 2005, pp. 1–42, https://doi.org/10.1533/tepr.2005.0003.

Ibrahim, N.A., El-Sayed, W.A. and Ameen, N.A. (2010), A novel technique to minimise energy and pollution in the dyeing of linen fabric. Coloration Technology, 126: 289-295. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1478-4408.2010.00263.x

Kiryluk, Aleksander, and Joanna Kostecka. “Pro-Environmental and Health-Promoting Grounds for Restitution of Flax (Linum Usitatissimum L.) Cultivation.” J. Ecol. Eng., vol. 21, no. 7, 2020, pp. 99–107, https://doi.org/10.12911/22998993/125443.

Lutton, S.C. “Background History of Linen from the Flax in the Field to Finished Linen Cloth.” Journal of Craigavon Historical Society, vol. 8, no. 1, Oct. 2009. https://web.archive.org/web/20200803042744/http://www.craigavonhistoricalsociety.org.uk/rev/luttonhistoryoflinen.html

Radchenko, Olga, et al. “Development of Options for the Implementation of the Technology of Manufacturing Linen Products, Combined with the Softening of Semi-Finished Products.” AIP Conference Proceedings, vol. 2430, no. 1, Jan. 2022, p. 090004, https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0077242.

Robinson, Michele Nicole. “Dirty Laundry: Caring for Clothing in Early Modern Italy.” Costume, vol. 55, no. 1, Mar. 2021, pp. 3–23, https://doi.org/10.3366/cost.2021.0180.

Ryszard M., Kozlowski, et al. “Future of Natural Fibers, Their Coexistence and Competition with Man-Made Fibers in 21st Century.” Molecular Crystals and Liquid Crystals, vol. 556, no. 1, May 2012, pp. 200–22, https://doi.org/10.1080/15421406.2011.635962.

Turner, John Anthony. Linseed Law: A handbook for growers and advisers. BASF United Kingdom Limited, Agricultural Business Area, 1987.

Yates, Luke, and David Evans. “Dirtying Linen: Re-Evaluating the Sustainability of Domestic Laundry.” Environmental Policy and Governance, vol. 26, no. 2, Mar. 2016, pp. 101–15, https://doi.org/10.1002/eet.1704.

Nithya Duggaraju

Jemima Jagger-Wells, Sofia Zurek

DES 40A

Professor Cogdell

Linen: Waste Produced During its Life Cycle

Linen is a breathable lightweight fabric made from natural materials that is often used for household items like bedsheets, tablecloths, curtains, and upholstery as well as garments. Mainly produced in China and some European countries, it is a little more expensive than most fabrics due to the complex process of creating it. There are four main types of linen with generally varying uses: Damask, plain-woven, loosely woven, and sheeting linen, all of which differ in how they are woven, but have a similar life cycle (Walls). Linen is a reliable fabric that lasts a long time if properly taken care of, which means that people do not have to replenish linens as much as other fabrics. Through the process of growing and harvesting flax, removing the fibers, spinning and weaving the fabric, transporting it, and maintaining it at home, linen is sustainable because there is relatively little waste produced. The main forms of waste in the life of linen are wastewater from the retting and dying process, carbon-based pollution from transportation, and some plastic and wastewater from laundry upkeep.

Creating linen starts with the flax plant which is grown in spring to winter and harvested after about 100 days. Linen cannot handle hot weather, so it is grown in cool damp weather. Harvesting takes place when the plant is somewhat withered and turns yellow (“How Linen Is Made”). Harvesting machines have CO2 emissions as they run on gas or diesel. For flax, one of the main machines used in the harvesting process is a rotary tedder used to spread apart the harvested plants, and it runs on fossil fuels (Gomez-Campos). Other than this, there are no other waste products because the small shives (wooden bits) left over from harvesting are left on the field to decompose (Gomez-Campos). It is worth mentioning that some higher quality linen is also harvested by hand around the world because machines often cannot pull the plants with their roots, which leads to longer fibers and stronger fabric (“How Linen Is Made”). Therefore, this type of high-end linen does not have the same carbon footprint as mechanically farmed ones. However, the majority of commercial linen is harvested by machinery that uses fossil fuels to function. After harvesting, the plant can be prepared for creating the fabric and weaving.

The bark of the flax plant needs to be removed through retting, scutching, and breaking, and the leftover fibrous material must be spun into fabric. Retting is the process where the pectin of the flax plant is broken down to separate the outer part from desired inner bast fibers. To do this, the plant either goes through water-based retting or chemical retting, but in modern day, chemical retting is more common because it is faster. Water retting produces no waste because the plant is submerged in water bodies and the bacteria in the water naturally break down the pectin. Dew retting is when the plants are left in the fields to be exposed to dew, which has the same result (Akin). In chemical retting, the flax is boiled in alkali or oxalic acid to achieve this (Yu et al.). Chemical retting has downsides however, because it lowers the quality fabric by weakening the fibers and results in wastewater. The water used is polluted with alkali chemicals and runs into natural water bodies. It also can make the separated bits like stalks that are unnecessary for linen toxic by imbuing them with chemicals (Akin). The outer wooden stalks are further removed by crushing them through rollers and then putting them through a scutching machine that removes the broken pieces. This waste is generally biodegradable. Also, the seeds and shives that are removed are used for other products. Flaxseeds are edible and make linseed oil that is often used for paints and cosmetics as well as linoleum to coat flooring (Akin). Shives are used for making lightweight wooden boards for building, animal bedding, insulation, and sometimes in potting soil (Gomez-Campos et al.). When spinning the fibers, there is dry and wet spinning. Wet spinning, used for longer fibers, may waste some water but this water is nontoxic (“Linen: A Precious, Zero-Waste and Sustainable Vegetal Fiber”). At the end of this long process, linen is ready to be shipped around the world.

Linen is mainly manufactured in China, as well as some European countries, so it must be transported through mostly cargo ships. Demand for linen exists all over the world, particularly for common items like bedsheets. On average, per metric ton of goods per kilometer, one cargo ship can produce 16.14 grams of CO2 (Kilgore). Bunker fuel oil of cargo ships contains sulfur which, when burned, releases toxic gas and fine particles which also impact human communities who live near the oceans by leading to negative health consequences (Gallucci). Not only do cargo ships emit black carbon that ruins air quality, but they also dump about 10 billion metric tons of wash water into the ocean every year. Wash water is a byproduct of burning bunker fuel that is highly toxic and filled with carcinogens, heavy metals, and nitrates (Gallucci). This causes harm to marine life and also often washes up near shores to affect humans. Therefore, cargo ships have devastating effects on the oceanic environment as well as the air. Although not responsible for all of this pollution, linen does contribute because it is transported on these same ships. After transport into a consumers’ home, linen must be taken care of.

Laundry and upkeep of linen produce some wastewater and plastic, but the fabric can last up to ten years if properly maintained. Therefore, its long-lasting nature makes it so that consumers do not need to buy and waste new fabric as often. When washing linen, laundry produces wastewater from the soap which pollutes freshwater rivers and lakes as well as the ocean. They normally have low biodegradability. Soaps have surfactants that often cause eutrophication of water bodies, harming the ecosystem (Santiago et al.). This means that the foam blocks oxygen from entering the water and leads to uninhabitable areas for marine life. If oxidizing agents are used in the soap to remove stains, it also results in some toxicity in the water (Santiago at al.). Plastics from detergent bottles go into landfills as well. Plastics are derived from fossil fuels like petroleum and will not decompose, but can be recycled (“The Life Cycle of Plastic Laundry Detergent Jugs”). However, it is important to note that waste from laundry upkeep is present for any material and this does not imply that linen particularly requires more laundry or soap than other fabrics. In addition to laundry, though a minimal effect, linen creases often and can be ironed a lot, which uses some electricity, which in turn likely was produced through some fossil fuel burning (“Linen: A Precious, Zero-Waste and Sustainable Vegetal Fiber”). After its life has run its course, when it is time to throw linen away, it will not produce much waste.

Linen can be repurposed and is generally fully biodegradable unless the fabric has been treated with chemicals. When recycling linen for other purposes, it can be used in papers, insulation materials, upholstery, and even mattress fillings (Sandin). If in good condition, it can also be shredded and respun to be reused in knitting or weaving new fabrics (Eco-Friendly Guide for Linen Recycling”). However, if thrown away, linen will generally biodegrade without any waste byproducts. To be biodegradable, a material has to be able to be broken down by microorganisms. Chemical dyes and treatments interfere with the biodegrading process because the microorganisms can only break down organic matter. Therefore, this can make the treated linen unable to fully decompose. Otherwise, if untreated, linen biodegrades in about two weeks (“Is Linen Biodegradable?”). Since the fabric by itself is directly produced from the flax plant with no synthetic fibers, it is able to decompose naturally. Overall, no waste is produced in the recycling and waste management process unless the fabric is chemically treated.

Linen is in general an incredibly environmentally friendly fabric that produces little waste. The main waste components are wastewater and CO2 emissions produced mostly from transportation but also from farming machinery. Wastewater from manufacturing this textile can be reduced by using methods like dew or water retting rather than chemical retting. Laundry also leads to wastewater and produces plastic, but this is true for any fabric and is not unique to linen’s life cycle specifically. Otherwise, the parts of the flax plant that are not used in making linen are either left to decompose or utilized in other products such as paints, linoleum, light wooden boards, or edible flax seeds in food. The byproducts of the life cycle are generally biodegradable, unless they have been chemically treated, which is why natural linen that is undyed and unbleached is the most environmentally friendly.

Bibliography

Akin, Danny E. “Linen Most Useful: Perspectives on Structure, Chemistry, and Enzymes for Retting Flax.” ISRN Biotechnology, U.S. National Library of Medicine, 30 Dec. 2012, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4403609/.

“Eco-Friendly Guide for Linen Recycling.” Home Decor And Crafts With Handkerchiefs And Linens, https://bumblebeelinens.com/blog/eco-friendly-guide-for-linen-recycling/.

Elamin, Abdelrahman, et al. “Fungal Biodeterioration of Artificial Aged Linen Textile: Evaluation by Microscopic, Spectroscopic and Viscometric Methods.” Zenodo, 2 Oct. 2018, https://zenodo.org/record/1461623#.Y-XhDOzMIe0.

Gallucci, Maria. “Cargo Ships Are Cleaning up Smog - by Dumping Pollution into the Seas.” Grist, 25 May 2021, https://grist.org/transportation/cargo-ships-are-cleaning-up-smog-by-dumping-pollution-into-the-seas/.

Gomez-Campos, Alejandra, et al. “Flax Fiber for Technical Textile: A Life Cycle Inventory.” Journal of Cleaner Production, 15 Dec. 2022, https://hal.inrae.fr/hal-03100886.

“How Linen Is Made.” Deck Towel, https://www.decktowel.com/pages/how-linen-is-made-from-flax-to-fabric.

“Is Linen Biodegradable? (and Compostable).” Conserve Energy Future, 22 Sept. 2022, https://www.conserve-energy-future.com/is-linen-biodegradable.php.

Kajaks, Janis, and Skaidrite Reihmane. “Thermal and Water Sorption Properties of Polyethylene and Linen Yarn Production Waste Composites.” Die Angewandte Makromolekulare Chemie 272.1 (1999): 24–26. Web.

Kazulis, V., et al. “Conceptual 'Cradle to Gate' Analysis of GHG Emissions from Wood, Agricultural Plant and Synthetic Fibres.” DSpace, 1 Jan. 1970, https://dspace.emu.ee//handle/10492/3918.

Kilgore, Georgette. “Air Freight vs Sea Freight Carbon Footprint (the Real Numbers in 2023).” 8 Billion Trees: Carbon Offset Projects & Ecological Footprint Calculators, 20 Jan. 2023, https://8billiontrees.com/carbon-offsets-credits/carbon-ecological-footprint-calculators/air-freight-vs-sea-freight-carbon-footprint/#:~:text=A%20cargo%20ship%20produces%2016.14,metric%20tons%20of%20carbon%20dioxide.

Lemmons, Richard. “Fossil Fuel Use in Agriculture - Plant Physiology.” Climate Policy Watcher, 3 Jan. 2023, https://www.climate-policy-watcher.org/plant-physiology/fossil-fuel-use-in-agriculture.html.

“Linen: A Precious, Zero-Waste and Sustainable Vegetal Fiber.” Manteco, 12 Jan. 2023, https://manteco.com/linen-a-precious-zero-waste-and-sustainable-vegetal-fiber/.

M.A. Hann. “Innovation in Linen Manufacture.” Taylor & Francis, 8 July 2010, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1533/tepr.2005.0003.

Radchenko, Olga, et al. “Development of Options for the Implementation of the Technology of Manufacturing Linen Products, Combined with the Softening of Semi-Finished Products.” AIP Conference Proceedings, vol. 2430, no. 1, Jan. 2022, p. 090004, https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0077242.

Sandin, Gustav, and G. Peters. “Environmental Impact of Textile Reuse and Recycling – A Review.” Journal of Cleaner Production, Elsevier, 27 Feb. 2018, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0959652618305985.

Santiago, Dunia, et al. “Laundry Wastewater Treatment: Review and Life Cycle Assessment.” ASCE Library, American Society of Civil Engineers, 1 Oct. 2021, https://ascelibrary.org/doi/epdf/10.1061/%28ASCE%29EE.1943-7870.0001902.

“The Life Cycle of Plastic Laundry Detergent Jugs.” Dropps, https://www.dropps.com/blogs/spincycle/the-life-cycle-of-plastic-laundry-detergent-jugs.

Walls, Bill. “Types of Linen Fabric For Your Project.” WORLD LINEN, 30 July 2020, https://worldlinen.com/blogs/news/types-of-linen-fabric-for-your-project.

Yates, Luke, and David Evans. “Dirtying Linen: Re-Evaluating the Sustainability of Domestic Laundry.” Wiley Online Library, 20 Apr. 2016, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/eet.1704.

Yu, C., et al. “The Physiochemical Alteration of Flax Fibers Structuring Components after Different Scouring and Bleaching Treatments.” Industrial Crops and Products, Elsevier, 25 Nov. 2020, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0926669020310293.