Design Life-Cycle

assess.design.(don't)consume

Gicel Abraham

Sara Galvis, Ethan Teano

DES 40A

Professor Cogdell

Wilson Football Lifecycle: Raw Materials

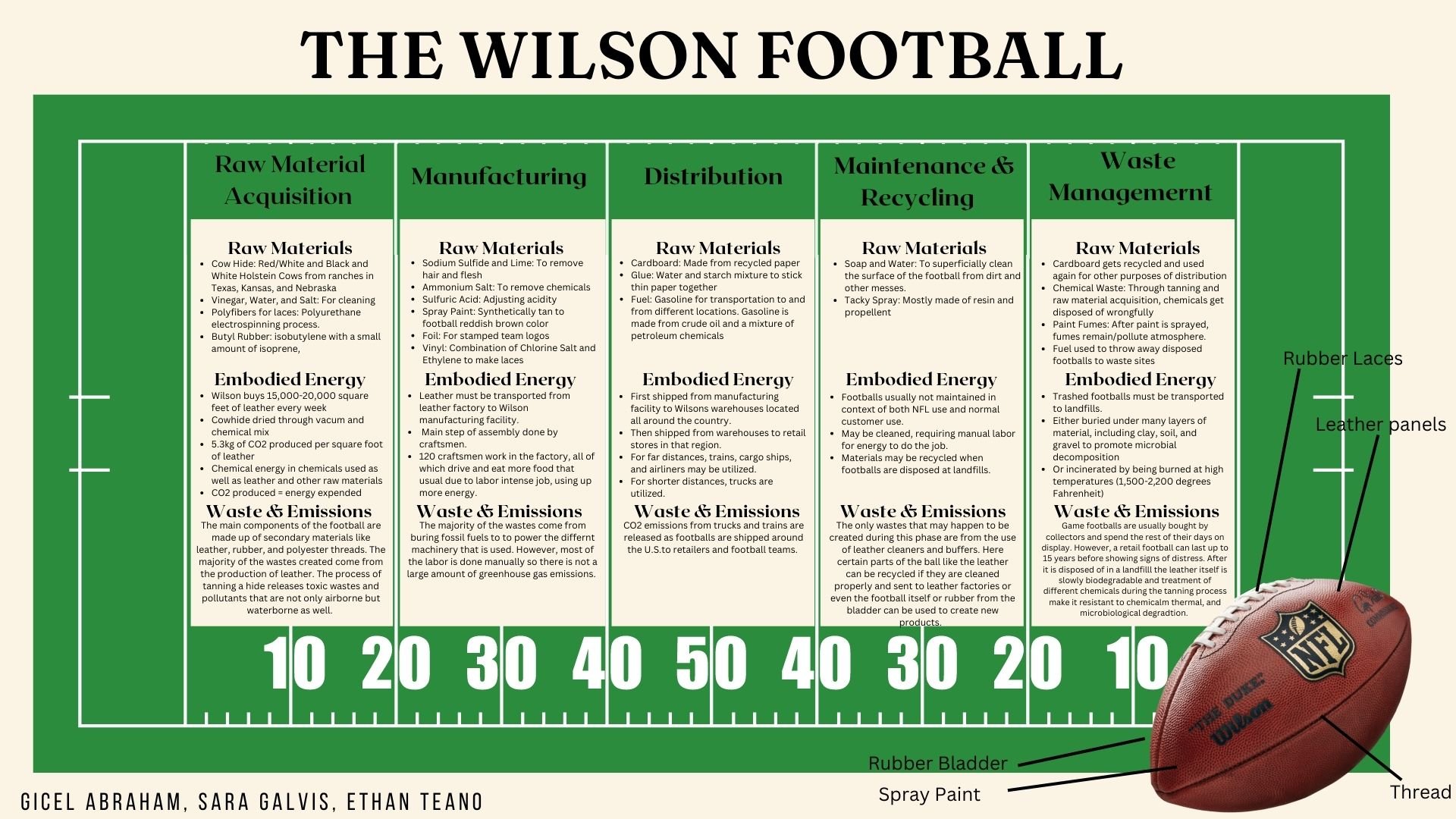

The American football has been around as far as the 1850s. The game is an evolution from rugby that started on college campuses. Colleges such as Harvard and Duke were one of the first colleges that started playing football for the first time, as they started to kick a rugby ball. From there the journey of creating the football began. Initially, it was covered in pig bladder, shaped like a 3D oval that was inflated via the mouth. However, it was not the most durable design as it was prone to leaks and holes. For years the design of the football has been redeveloped to complement the changing rules of the game. The standards were basically set in the 1930s when the National Football League (known hereafter as NFL). Through time, the material used in footballs has drastically changed to fit the safety and player needs. Now, the Football is a staple of American entertainment. Fans around the world come together to watch their teams throw this elongated sphere around and tackle each other. People are so focused on the moment right when the receiver runs down the field to the touchdown, no one thinks about the origins and lifecycle of the football itself. While a football is glorified in the prime of its lifecycle, a lot goes into making it and where it ends up after the game ends. A football’s lifecycle is very overlooked, however, it is important to study its sustainability due to the rate at which the NFL uses them. Examining a football from a life cycle perspective, the accumulation of raw materials weighs heavily on the environmental impacts.

Like all life cycles, it starts with acquiring the core earthy materials to start the process. One of the main and most important parts of the football is the iconic leather that envelopes the ball. With a very controversial origin story, it is necessary to discuss all the acquisition processes of the various raw materials. The leather is obtained from Holstein cows in various farms and ranches in Texas, Kansas, and Nebraska. Cows are raised and fed about 30 pounds of grain a day according to an interview conducted by Sports Illustrated. After they are fully matured and big enough, they are jabbed and shoved into a small quartered trailer to be taken to the slaughterhouse. After that process, the workers have to carefully separate the hide from the meat using a mechanical hide puller. This machine allows the hide to evenly peels off the muscles and allows for no nicks or sores. If it has any nicks or sores, it would not be a viable football. They are then cleaned and cured using a mixture of vinegar to kill all the bacteria. They are then placed in a bucket to soak in water and salt for 24 hours. After it is rinsed, it gets rubbed down with dry salt and left there for 2 weeks. Lastly, it is left in the sun to dry completely. Finally, they are rolled up and placed into the truck, and shipped off to the tannery. Another important material used in the creation of the football is the threads and strings that tie all the leather together. The white threads that give the football its iconic look are made from either rubber or poly fibers. The poly fibers are made primarily out of polyurethane. Polyurethane is a synthetic resinous, fibrous compound. It is best known for being lightweight and having elastic qualities. Polyurethane is made from a mixture of glycol and diisocyanate and is produced via electrospinning, a method of applying an electric field on charged glycol/diisocyanate polymers with a jet of polymer solution that elongates the polymers to create the fibers. One final material that composes a football is the rubber bladder inside the leather encasing to fill up the ball with air. This rubber bladder is usually made from butyl rubber. Butyl rubber is a synthetic rubber produced by combining two substances, isobutylene with a small amount of isoprene, to form a polymer through chemical reactions. Butyl rubber is great at retaining air thus why it is used in footballs compared to natural rubber. Once acquiring all of the primary raw materials needed, it is time to assemble them all together to create a full product.

While the manufacturing process consists of building the football, it also introduces new material that gets added to the complete state before it gets shipped to the consumer. One of the first stages in manufacturing a football is to tan. The main tannery that works with Wilson Co. which makes the NFL footballs, is Horween Leather Co. The first step is to remove the flesh and hair from the leather using a mixture of sodium sulfide and lime. This leaves just the thin leather. The main tanning process is 3 steps: bate, pickle, and tan. Bating is an enzyme wash, a mixture of an ammonium salt and proteolytic enzymes, to remove any unwanted chemicals and extra hair while also making the leather soft. Pickling is treating the leather with a sulfuric acid solution that is used to adjust the acidity before tanning. The final step is to tan the hide using a chromium salt mixture which turns the hide into a light blue color. They are then dried and sorted based on the quality after all of these processes. The hides are then placed in a huge drum where they spin around in high heat for 12 hours until they get a beige-tan color. Finally, they are sprayed with a deep reddish brown paint. Not many sources state which paint or what type is used. This is just the beginning of the manufacturing process. The leather is now sent over to Wilson headquarters in Chicago to be assembled.

Arriving at the Wilson factory, the leather gets rolled out to the large tables. Each sheet of leather gets punched out by metal stencil cutters. It is to be noted that each football comes from the same leather sheet. Next, they get transferred to the “stampers” team where they press on shiny colored foil designs such as the NFL shield onto the leather. The foil is usually thin and multicolored that are layered on top of each other using a hot machine. Once those are stamped on they get moved to the stitchers. The “stitchers” sew each leather piece together inside out with the brown poly thread. Doing them inside out will make them seem invisible and less likely to get ruined through wear and tear. After the “stitchers” assemble the pieces together, the football gets passed on to the “turners”. The “turners” have the strenuous task of turning the ball right-side out. To make the task easier, they use a steam box to loosen the leather. This helps with hammering out the pointy ends of the football and making it right-side out. The “lacers” then add in the butyl rubber bladder inside the ball and lace up the ball with the iconic white laces that we see today. The white laces are made with the same material as the butyl rubber bladder or through vinyl depending on the quality of the leather being used. Vinyl is composed of chlorine salt and ethylene from crude oil. Once the football is all laced up, it is ready to be inflated. Manufacturers inflate the balls to 13 psi with atmospheric air. Many teams come by to inspect each ball to make sure it meets all the requirements. Depending on the quality of each ball, they get sent to different places. The “creme de la creme” of the batch gets sent to professional agencies such as NFL teams. The mid-tier rated footballs get used for general practices for teams and groups. The third-tier footballs or the ones that have some imperfections get shipped to retailers and regular buyers. After the inspection, all the footballs get sent over to get packaged and distributed.

There are various secondary materials used for the packaging and distribution of the football to the consumer. Packaging usually consists of cardboard cube housing and hard paper holders to keep the football still inside. Cardboard is made from recycled paper where a wavy layer called a flute is sandwiched between two flat layers of paper. They are stuck together by glue that is made from water and starch. The cardboard is then molded with the fold linings and cut out any handles that the packaging may have. The excess pieces are then taken back to the plant to be recycled. After inserting the football into the packaging, it is time for the football to meet its owner. Throughout the lifecycle of the football, the material got moved to different facilities via trucks and cars. These modes of transportation require fuel in order for them to get to where they need to be. Gasoline is made from crude oil and a mixture of petroleum chemicals that are entirely made up of hydrogens and carbon atoms. When the hide from the farms got transferred to the tannery, then to the Wilson facility, then shipped directly to the consumers, all of these movements used gasoline in order to get there. While not very environmentally friendly, it is the “easiest” way to move each football to its new location. Once it gets shipped to the consumer, there are materials needed to maintain the integrity and quality of the football.

Maintaining a Wilson football is very important, especially for the NFL, and requires new material to be introduced into the mix. After the wear and tear of throwing and kicking the football, even after a year of it sitting on the shelf, the ball starts to lose air over time. Consumers need to pump atmospheric air into the ball. Through many uses, the ball starts to get dirty from the ground/grass that it touches. Consumers are advised to clean their footballs using soapy water and a microfiber towel. It is important to keep it dry at all times so that the moisture does not deteriorate the leather. Especially for professional players, each person has their own way of how they like the football to feel. Many players like to add tacky spray onto their footballs in order to have a better grip and handle on the ball itself. Tacky spray was a very hard material to find the raw ingredients for. However, there was one materials list that had a generic spray with its ingredients. According to a google patent from researchers in China, “the [generic] spray adhesive comprises the following ingredients: 1-12 wt% of rubber, 1-5 wt% of dispersant, 10-40 wt% of tackifying resin, 10-60 wt% of varsol, 10-55 wt% of chlorinated solvent and 35-70 wt% of propellent.” These materials are used to keep the football in perfect condition and allow for it to last longer. Maintenance is key to extending the life of your football, however, there is eventually an ending to its long life.

After many fumbles and football-slamming touchdowns, many balls start to lose their quality and integrity past the point of no return. Depending on the quality of the football they eventually disposed of or donated it. When footballs get donated, it extends their life for another couple of years. However, there are times when it cannot be salvaged, and thus have to be disposed of. Many of the materials that are used throughout the lifecycle of a football have either positive or negative effects on the environment. As stated above, the packaging that is used to house the football is made from recycled paper and can continue to be recycled. While the leather itself isn’t recyclable, the meat that it came from gets used to feed millions of families around the United States. The butyl or vinyl materials used for the laces and bladder are not environmentally friendly and are actually the most toxic of all the materials listed through the lifecycle process. When the paint is sprayed during the tanning process, the fumes are very harmful to the people applying the paint. They end up staying in the surrounding air/atmosphere which is very dangerous. All the chemicals used during the leather acquisition and the curing/tanning process are not absorbed by the leather completely. There are various points where the leather is submerged in a bucket of chemicals. After this is done, the chemicals just get disposed of down the drain or into the ground. Many people do not know how to properly dispose of these chemicals which devastatingly harm the environment and any other raw materials that are acquired from the earth. The spray adhesive has no toxins and no pollution and can be used on white fabrics without yellowing or blackening with an ideal bonding effect. Viewing the overall effects of making a football, it does more harm than good and does not have a circular cycle. It has a more linear life from cradle to grave. Ideally, we want products that have a more cyclical cycle, however, there are certain materials that follow this ideal cycle.

Throughout the lifecycle of a football, there are various raw materials that get introduced at various stages of its development. Many of these materials do not get recycled, and thus immensely affect the environment. However, it was interesting to see that there are still some materials that did get their own little lifecycle within the football’s lifecycle.

Bibliography

“Ada, Ohio, the Town Where Footballs Are Born - Sports Illustrated.” Sports Illustrated, https://www.si.com/nfl/2018/01/28/super-bowl-52-ada-ohio-wilson-football-plant

Bell, Sharon M. “How to Metal Coat an Animal Skull for a European Mount.” Synonym, 17 June 2020, https://classroom.synonym.com/metal-coat-animal-skull-european-mount-10042690.html

“Butyl Rubber.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., https://www.britannica.com/science/butyl-rubber

EPA Regulatory Modeling Applications. https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2020-10/documents/mmgrma_0.pdf

EPA. “Toxics Release Inventory (TRI) Guideme.” EPA, Environmental Protection Agency, https://ordspub.epa.gov/ords/guideme_ext/f?p=guideme%3Agd%3A%3A%3A%3A%3Agd%3Aleather_4_2.

From Thermo Fisher Scientific – Materials & Structural Analysis, et al. “An Introduction to Vinyl.” AZoM.com, 18 Apr. 2019, https://www.azom.com/article.aspx?ArticleID=987#:~:text=Vinyl%20is%20composed%20of%20two,chloride%20monomer%20(VCM)%20gas

“Gasoline Fact Sheet.” Illinois Department of Public Health, http://www.idph.state.il.us/cancer/factsheets/gasoline.htm#:~:text=Gasoline%20is%20a%20mixture%20of,%2C%20toluene%2C%20and%20xylenes.

Golden, Jessica. “How It's Done: The Making of an NFL Football.” CNBC, CNBC, 29 Jan. 2015, https://www.cnbc.com/2015/01/29/sporting-goods-co-football-manufacturing-facility-ahead-of-super-bowl-xlix.html#:~:text=Wilson's%20footballs%20are%20made%20from,for%20more%20than%2040%20years.

Horween, Nick. “By Request - What's the Difference?” Horween Leather Co., Horween Leather Co., 27 July 2020, https://www.horween.com/blog/2010/12/14/by-request-whats-the-difference.

How Football Is Made - Material, Used, Machine, Raw Materials, Design. www.madehow.com/Volume-3/Football.html.

“How It's Made - Cardboard Boxes.” YouTube, YouTube, 7 Aug. 2013, https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=159&v=HL2yvqSk8Ww&embeds_euri=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.google.com%2F&source_ve_path=MjM4NTE&feature=emb_title&ab_channel=InternationalPlastics

“How to Clean Your Leather and Composite Footballs, Basketballs, Volleyballs and Soccer Balls.” Wilson Sporting Goods, 13 Sept. 2022, https://www.wilson.com/en-us/blog/all-sports/wilson-labs/how-clean-your-leather-and-composite-footballs-basketballs-volleyballs.

Insider. “How NFL Footballs Are Made.” YouTube, 20 Jan. 2018, www.youtube.com/watch?v=zGzY0wQHz1g.

Kahler, Kalyn. “Super Bowl 2019: How Cows Become NFL Footballs - Sports Illustrated.” Sports Illustrated, 2019, https://www.si.com/nfl/2019/01/31/how-cow-becomes-football-horween-wilson.

Manager, Content. “How to Make a Leather Football Tacky?” LeatherProfy, 22 Aug. 2022, https://leatherprofy.com/how-to-make-a-leather-football-tacky/.

“NFL Football Operations | NFL Football Operations.” NFL, 2018, https://operations.nfl.com/media/3277/2018-nfl-rulebook_final-version.pdf.

“Polyurethane Fiber.” Polyurethane Fiber - an Overview | ScienceDirect Topics, https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/chemistry/polyurethane-fiber.

“Super Bowl 2019: How Cows Become NFL Footballs - Sports Illustrated.” Sports Illustrated, https://www.si.com/nfl/2019/01/31/how-cow-becomes-football-horween-wilson.

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. “Butyl Rubber | Chemical Compound.” Encyclopedia Britannica, 22 July 2009, www.britannica.com/science/butyl-rubber.

Waxman, Olivia B. “Super Bowl History: Why Are Footballs Shaped like That?” Time, Time, 1 Feb. 2019, https://time.com/5515951/football-shape-history/.

“Wilson Football Factory - Ada, Ohio.” Factory - Ada, Ohio, 6 July 2022, https://www.wilson.com/en-us/explore/football/ada-ohio-factory.

Zukerman, Earl. “This Date in History: First Football Game Was May 14, 1874.” McGill Channels, 3 Sept. 2012, https://www.mcgill.ca/channels/news/date-history-first-football-game-was-may-14-1874-106694.

吕大洋 , and DONGGUAN DAYANG CHEMICAL CO LTD. “CN102277130B - Spray Adhesive Formula and Technology Thereof.” Google Patents, Google, https://patents.google.com/patent/CN102277130B/en.

Ethan Teano

Sara Galvis, Gicel Abraham

DES 40A

Professor Cogdell

Analysis of Energy Usage of a Wilson Football

When people think of America, one of the first things that come to mind is football. American football is one of the most loved and watched sports in the world and has been constantly evolving since the founding of the NFL. However, there has been one aspect of football and particularly the NFL that has remained constant over many decades: the use of Wilson Footballs. The brand Wilson became the official supplier of footballs for the NFL in 1941 and has never stopped since. Over the years, Wilson became regarded as the manufacturer of the highest quality footballs that one could buy. As a result, they don’t just supply the NFL for footballs, but now also the CFL, UFL, AAF, and the notorious NCAA. However, most of the Wilsons revenue comes from regular people buying their footballs, which can be bought in almost every sporting goods store. As a result, Wilson manufacturers about 700,000 new footballs every year (CNBC). Yet, there is one aspect that people often forget about when thinking about giant companies like Wilson. Yes, they enable people to play football and have a good time, bringing people together. However, it is often overlooked the effect of manufacturing this amount of product every year has on the environment. Particularly, how much energy is required to acquire the raw materials, to manufacture, to distribute, and then maintain, recycle, and waste manage 700,000 new footballs every year. The amount of volume that Wilson is manufacturing every year makes it an ideal company to research the energy required to fuel raw material acquisition, manufacturing, distribution, and waste management.

It is important to understand the energy input needed for a large company like Wilson to acquire the raw materials needed to make the huge volume of product they make every year. For instance, every week, Wilson buys 15,000-20,000 feet of cowhide from a leather manufacturer based in Chicago (Sage-Answers). It is hard to imagine how much leather this is and how much energy required to make this, however, according to (circumfauna), every square meter of leather produces 17.0kg of CO2. Converting this ratio to feet yields about 5.3kg CO2 produced per square foot of leather. This number multiplied by 15,000-20,000 for just one week gives an idea of just how much CO2 is being produced and therefore energy expended to make the leather for Wilson Footballs. Note this is only gives an idea of how much combustion energy is being used in the production of leather and doesn’t consider other energy sources that do not produce CO2. After raw materials have been acquired, the next step in the production process is to manufacture the football.

It is crucial to understand the energy input of the manufacturing process because it is the main step the creation of the football. First the raw materials must be transported to a manufacturing facility in Ada, Ohio.( WILSON FOOTBALL - 50 Built) This requires the use of trucks and trains to transport the many thousands of square feet of leather and other materials to the factory. Once the raw materials have reached the factory however, the footballs are handmade by craftsmen who carry out each step of turning the raw materials into a Wilson Football, (Wilson Footballs: Made in the USA (labor411.org)). This doesn’t mean that using people over machines is more energy efficient. Craftsmen do utilize machinery that mainly run off electricity (Secret Base), yet the majority of work is done through manual labor. Just because the footballs are handmade however doesn’t mean it is energy efficient. Using people instead if machines means Wilson must hire a lot of people, 120 people in the Ada Ohio factory to be exact (IDSWATER.com). Each of these individuals drive from their homes to the factory, and they eat more food than they would if they didn’t have a labor intense job. It’s hard to say if this is more energy efficient than machines, but it’s important to think of how people over machines effects energy input having required in production. Once the footballs have been made, the next step and potentially the most energy dependent step is the transportation/distribution of the footballs.

Wilson is a huge company and essentially has a monopoly on the football production industry. 700,000 balls a year and sold in almost every Target, Walmart, Dicks Sporting Goods, and many other sporting goods stores in the country makes distribution a very challenging and energy dependent job. The first step of the distribution process is for the footballs to be shipped from the manufacturing facility to Wilsons many warehouses located all around the country. The footballs can be shipped through trucks for shorter distances, and trains for longer distances. For international shipment, the footballs may be transported through cargo ships or airliners. Next, the footballs are shipped again from the warehouses to retail regional retail stores. Then, the footballs are put on display and bought by customers, who drive the balls to their homes or sporting parks to be used. Overall, the balls may be transported thousands of miles from the time they are made to the time they are bought by the customer, taking tons of energy. It’s hard to know the exact number of miles each ball travels and how many stores sell Wilson Footballs. However, there are a total of 21,000 sporting goods stores in the United States (Sporting Goods Stores Industry Profile from First Research) and since Wilson Footballs being the most popular brand for footballs, it’s safe to say that they are most likely sold in a majority of these retail stores. Once the footballs have been manufactured, shipped, and bought by customers, the main energy dependent steps of the life cycle have already occurred. Yet, there is still one more step in the life cycle of a football that requires energy, waste management.

After the footballs have been bought, most customers use the ball for a few years or so until the ball becomes too worn down to play with, then the customer throws the old ball away and goes out and buys another one. There is not much maintenance done by the average person for their footballs. The NFL is especially wasteful in their use, each team is given and goes through 108 footballs every season (Disposal | Wilson Football Commodity Chain (osu.edu) ). Wilson themselves does not state any plan or method for recycling their footballs. Therefore, waste management is the next energy intensive step in the life cycle. It’s hard to know the rate at which people go through footballs, or the time between people buying the balls and throwing them away. But if we assume all footballs bought will be thrown away, that leaves a huge amount of waste as well as energy needed to process and dispose of that waste. The first step after the footballs have been thrown away is for them to be transported to a local landfill. Again, requiring the use of big, energy dependent trucks to transport them. Then, it is buried in many layers of material, including soil, clay, and gravel in order to prevent waste from coming into contact with groundwater, as well as promoting the decaying process of the waste. This step is also very energy dependent as it takes lots of energy to operate heavy machinery to dig large holes for the waste as well as stack the many layers of material required. These methods overall produce methane gas as well as a substance called leachate. Both are harmful to the environment and many landfills have processes to collect these substances, requiring even more energy. Another, yet less common method of waste management is incineration. This process is when waste is loaded into a machine called an incinerator and burned at very high temperatures, usually between 1,500-2,200 degrees Fahrenheit. As one could imagine, this takes a huge amount of energy to be able to make a large amount of waste reach these extreme temperatures.

As stated before, Wilson is a very large company and has a huge monopoly on the football industry. Producing 700,000 new footballs every year has massive implications on the environment, which makes it very important for people to understand the life cycle of the product Wilson is producing. It is often overlooked how much goes into every step of the life cycle. The many steps and energy expended for raw material acquisition. The manual labor for the manufacturing step in the factory. The vast network of trains and trucks and potentially airliners and cargo ships to transport the footballs from the factory to the many warehouses, and then to even more retail sporting goods stores. And then lastly the complex and very much energy dependent waste management process that goes into disposing of all products we use. It’s essential to comprehend the life cycle of a Wilson football because it serves as a good example of how much energy and resources are used to create the products that we take for granted. Many people don’t realize the impact they have on the environment but learning about the life cycles of small things can help them understand their impact better.

Bibliography

1. “Manufacturing Process of Wilson Footballs”, OSU.Ed, 2021, Manufacturing Process | Wilson Football Commodity Chain (osu.edu)

2. “Sustainability Playbook Initiatives”, NFL Green, NFL Green | NFL.com

3. “How is a Football made”, September 10, 2018, W.N.SHAW&CO, How A Football Is Made - The Football Manufacturing Process (wnshaw.com)

4. Nick Smith, “Behind the Scenes: How NFL Footballs are Made”, NEWSNATION, February 12, 2022, How NFL footballs are made (newsnationnow.com)

5. Claudia Timm, “Sustainability: Sports Brands Choose Different Strategies” Ispo.com, March 2019, Sustainability in Sports Business: Recycled, Durable and PFC-Free (ispo.com)

6. “Sustainability Report Championing Sustainability”, Informa, Sustainability Reports (informa.com)

7. “Sports Good Manufacturing”, MarketResearch.com, February 2023, Sporting Goods Manufacturing (marketresearch.com)

8. Ford Mcmurty, “What does the NFL do with used balls after the game?”, Quora, 2018, What does the NFL do with the used balls after a game? - Quora

9. “Big Game USA Factory Info” BigGameUSA, 2023, About - Big Game USA

10. “10 ways the world of sports is tackling plastic pollution” UN Environment Programme, May 2018, 10 ways the world of sport is tackling plastic pollution (unep.org)

11. “Leather Industry Data Shows us it is Far More Impactful than even Synthentic Alternatives” CIRCUMFAUNA, Leather carbon footprint — C I R C U M F A U N A

12. “Wilson Footballs: Made in the USA” Labor411, December 2017, Wilson Footballs: Made in the USA (labor411.org)

13. “Sporting Goods Stores Industry Profile”, dun&bradstreet, February 2023, Sporting Goods Stores Industry Profile from First Research

14. “Wilson Football Commodity Chain”, Ohio State University, Disposal | Wilson Football Commodity Chain (osu.edu)

15. “How its done:The making of an NFL football”, January 2015, CNBC, The Wilson Sporting Goods Co. football manufacturing facility shows how it's done (cnbc.com)

16. “Wilson Football Facotory: The Pride of Ada”, September 2019, SpectrumNews1, Wilson Football Factory: The Pride of Ada (spectrumnews1.com)

17. “Wilson Factory Ada Ohio tour” July 2019, IDSWATER, Can you tour the Wilson Football Factory in Ada Ohio? – idswater.com (ids-water.com)

Sara Galvis

Group: Gicel Abraham, Ethan Teano

DES 40A

Professor Cogdell

The Life Cycle of the Football: Wastes and Emissions

American Football; the epitome of American Sports and Society. Americans across the country are brought together to watch this sport which consists of 2 teams of massive players trying to get an oval-shaped ball across their opponents' end of the field, tackling each other as they fight to stay in the lead. Even though this sport is played professionally, most American families own footballs which they throw around in their backyards with their kids. Can we even account for the number of footballs that exist within the U.S.? Almost 3,000 footballs are produced daily, and manufacturers like Wilson produce 500,000 balls each year( Kahler, 2019). The impact of this small ball is overlooked. When delving into the realities of the sustainability of the lifecycle of the football, we will discover its impact is not as small as we may think.

The materials, energies, and processes used in the production of a Wilson Football threaten its sustainability and inherently create large amounts of waste and emissions. However, here I will delve into the specifics of the waste created during each part of the football's lifecycle; during the acquisition of raw materials, manufacturing, distribution, maintenance, and waste management.

Let's start at the beginning of the story; what materials are used to make the Wilson football? Let's take a look at the raw primary and secondary materials and the energy and wastes involved in acquiring these materials. The main raw material used in football production are cow hides, a primary material, which are then processed into leather, a secondary material. The cowhide usually comes from ranches in Texas, Kansas, Nebraska, or Ontario. However, for NFL footballs, the cowhide comes from a much smaller farm in Pandora, Ohio, called "Rodabaugh Bros. Meats." This small farm works with Horween, the leather tannery that processes the hides in Chicago. They say that one hide can produce fifteen to twenty footballs. The secondary raw material that comes from the hides is leather, precisely four leather panels. Hides are processed at the Horween Leather Company in Chicago. It is the only tannery that turns hides into leather for Wilson. Wilson buys 15,000- 20,000 feet of cowhide per week. The production of leather is broken down into three processes, the preparatory stage, the tanning stage, and the crusting stage; these take three weeks. First, the hide undergoes hair and flesh removal using an industrial-strength nair ( sodium sulfide and lime). Then the hide undergoes a three-step tanning process: bate, pickle, tan. The bate uses an enzyme wash. Pickling is done with an acid pre-tan solution. Finally, tanning uses a chrome mix that turns the hides into a shade of light blue. Hides are then split into two pieces and shaved down to uniform thickness. Then they are re-tanned inside a metal drum that rotates for eleven hours at twelve rpm. Once the hides are dry, they are embossed by a 57,000 press with a specific design used by Wilson. Finally, the leather is spray tanned, a deep reddish brown hue typical to an NFL football.

Throughout the process, from cowhide to leather, we encounter many wastes. At the root, we have cattle farming which contributes to GHG emissions from animal wastes and cattle feed production. Although we do not have precise data, we have been able to derive from research that the tanning processes contributes significantly to chemical oxygen demand (COD), total dissolved solids (TDS), chlorides, sulfates, and heavy metal pollution. According to a journal, "The Toxic Hazards of Leather Industry," enormous amounts of water and pollutants are discharged during the entire tanning process. This wastewater can contain harmful chemicals such as chromium, synthetic tannins, oils, resins, biocides, and detergents. The pre-tanning process results in variations in pH and causes increase in chemical oxygen demand (COD), total dissolved solids (TDS), chlorides, and sulfates in tannery wastewater. The conventional de-hairing process with sodium sulfide and lime accounts for 84% of biochemical oxygen demand (BOD), 75% of COD, and 92% of suspended solids (SS) from a tannery. The post-tanning process also results in modifications in TDS, COD, and heavy metal pollution ( Dixit, S., Yadav, A., Dwivedi, P. D., & Das, M., 2014). They have found that conventional pre-tanning and tanning processes account for nearly 90% of the total pollution from a tannery. In terms of airborne wastes, pollutants such as ammonia, hydrogen sulfide, volatile hydrocarbons, amines, and aldehydes are emitted to the atmosphere from tannery plants as effluents. Ammonia emissions may occur during de-liming, de-hairing, or drying processes, while sulfide emissions may result from liming/ unhairing and subsequent processes. Hydrogen sulfide is released in tannery wastewater from alkaline sulfides if the pH is less than 8.0. Particulate emissions contain chromium, which may occur due to the reduction of chromate or through the handling of basic chromic sulfate powder, or from the buffing process. Thus substantial amounts of volatile organic compounds (VOC) are emitted during different tanning processes, which may threaten the atmosphere if not controlled properly ( Dixit, S., Yadav, A., Dwivedi, P. D., & Das, M., 2014).

The disposal of solid wastes is another problem that is usually overlooked. In this case, putrefied hides/ skins, raw trimmings, and salt each release 624 kg of CO2 for each ton of waste. Other wastes release similar amounts of CO2 emissions for each ton. They also say, "A great deal of sludge generated from the tannery plants render the solid waste management system highly inactive due to non-biodegradability of the tanned leather." and say, "Leather itself is slow biodegradable, and treatment of different chemicals during the tanning process makes it resistant towards chemical, thermal, and microbiological degradation." Two methods are proposed in the article for reducing the negative environmental impact of hide processing. The first method is termed as low-waste or cleaner technologies that avoid the use of harmful chemicals and produce solid wastes which can be used as byproducts. The second method is related to wastewater treatment and the environment-friendly handling and processing of solid waste. The methods applied in both groups can be used to prevent leather production with a less negative impact on the environment( Dixit, S., Yadav, A., Dwivedi, P. D., & Das, M., 2014).

We can also analyze the process of acquiring other secondary materials like the rubber bladder, rubber laces, thread, and spray paint. The rubber bladder is made from either natural or synthetic rubber. The raw material is heated and forced into a mold, forming a balloon. As the material cools, it wrinkles, and workers will remove the bladders from the mold and partially inflate them to smooth them out ( Kahler, 2019). Through rubber production, chemical dusts come into contact with the air, and some get contaminated in water; therefore, directly or indirectly affecting living things. Because of this, waste management is a major concern in the rubber industry( Mohsenirad, Fataei, 2020). Based on findings in the "Life Cycle Assessment of ball bladder production with and without recycled rubber," we are informed that "the ball bladder with natural rubber had the largest contribution to the ozone layer depletion (39.2%) and global warming (41.1%), while the bladder with both recycled and natural rubbers had an impact of 27.9% and 29.5%, respectively". The thread is a braided brown poly thread and a brown wax-lined polyester thread. Polyester is usually made using fossil fuels. Although these threads are probably the most biodegradable components of the football, they are not produced in a way that spares the environment harm. The laces are also usually made of rubber, specifically Nitrile butadiene rubber. Nitrile Butadiene Rubber ( NBR) is a petroleum-based, oil-resistant synthetic rubber( Monmouth Rubber and Plastics Corp, 2021). There are currently several ways in which the environmental impacts of NBR are being mitigated: reduction in greenhouse gas emissions, introduction of renewable sources of feedstock in production, and limiting landfill buildup. Many organizations are focusing on using renewable energy during the manufacturing process to diminish greenhouse gas emissions. Due to high prices and a declining supply of petroleum, there is also a push to produce rubber that is not sourced from petroleum and instead from bio-based feedstock. For example, butadiene, a key ingredient of NBR, can be produced with renewable raw material sources such as non-food biomass. According to Monmouth Rubber and Plastics Corp., rubber, leather, and textiles make up as much as 8% of all landfills. Synthetic rubber waste comes from discarded used products and as a byproduct of manufacturing. Recycled rubber products can be a solution to reducing landfill waste; they are more cost-effective and eco-friendly as their production takes non-biodegradable waste out of the environment ( Monmouth Rubber and Plastics Corp, 2021). Although the effects and wastes of the specific spray paint used to color the leather are not precisely known, we know that these types of aerosols are proven to impact the ozone negatively because of the volatile organic compounds (VOCs) and hydrocarbons which are frequently found in them.

Now let's delve into the production of the football itself and the wastes created during this process by machines, specifically energy outputs. The Wilson plant, where footballs are made, is located in Ada, Ohio. The plant can process up to 3,000 balls every day. Surprisingly, almost the entire production of the football is done by hand over a three to five-day process. The making of each ball can involve some two dozen people. As told by Sports Illustrated in their article, 'How cows become NFL footballs", there are cutters, stampers, stitchers, turners, lacers, molders, inspectors, and packagers. Stampers take panels and insert them into a machine that presses a shiny foil design of the NFL shield onto the leather. Stitchers use old fashion, union lockstitch sewing machines manufactured by Campbell Randall Leather Machine Company( in business since 1858) to sew the four panels together inside out (so the seams don't show). They use two types of strong thread a braided brown poly thread and a brown wax-lined polyester thread. The sewing is so intricate that it can take a new employee 3-5 months to perfect the technique. Turners take the inside-out shells and wrestle them right side out. They soften the balls in a steam box and hammer in the two pointy ends of a football. They do this by placing one end on the top of a pole attached to a table. They use the pole for leverage to work the leather right side out by pulling it through the gap where the laces will go. Each turner can flip 500-600 balls a day. It is the most physically demanding job. The lacers will place a rubber bladder inside the ball and double-lace each ball closed. Their fingertips are wrapped in white athletic tape to grip the rough leather better. Molders will then inflate the footballs to 13 PSI inside a special mold.

Let's carefully analyze the wastes created by each of the machines and materials used throughout the production process. First, we can look at the heat press that presses the NFL design onto the leather. Although there is not enough information to know exactly how much waste is generated through energy use, we can deduce that heat is used to emboss the design onto the leather and electricity since it seems the machine is automatic. The next step of the process involves the use of union lockstitch sewing machines. The sewing machine will consume energy for how long the pedal is pressed and at the speed at which it runs, which for this machine is 300 SPM( Campbell Randall). However, the specific wattage used for this machine is not provided by the manufacturer therefore, the energy wastes cannot be calculated. After this, the balls will then be softened in a steam box. Although the specifications of the steam box are not detailed anywhere, the machine uses about 9kw to function if compared to a similar steam machine used to soften leather shoes ( JSM auto). Next, the lacers lace each ball; while doing this, they wear athletic tape, which can be accounted for as a waste of the production process. According to an article published on Digital Sport, many traditional sports tapes contain environmentally unsound ingredients, such as acrylics, PVC, plastics, and synthetics, which do not break down naturally. As a result, there has been an increase in the use of disposable tape that creates negative effects on the environment, ending up in landfill and waterways after use. Finally, the balls are inflated. This is done using an industrial air compressor. Although it is not known how much energy is used by the ones used in the production of a football, it can be estimated, based on data from other air compressors, that a 110-volt compressor drawing 15 amps uses 1,650 watts (110 volts x 15 amps), while a 220-volt compressor drawing 15 amps consumes 3,300 watts (220 volts x 15 amps) (McCuhil,2012).

Something that is easily overlooked are the wastes created by the energy sources used. Are they releasing harmful emissions into the atmosphere? If we focus on the process of converting hide to leather, we can analyze the emissions created by a tannery based on the energy sources they use. Emissions will vary depending on the type of energy source used for the preparation of hot water to wet hides. According to a study done by the United Nations Industrial Development Organization, coal will release 2.14 kg of CO2 per meter squared, liquid fuel will release 1.51 kg of CO2 per meter squared, and gas 1.28 kg of CO2 per meter squared. In order to reduce the amount of emissions, manufacturers can use more efficient equipment, for example, low-speed drums instead of high-speed drums, green fleshing, splitting in lime, and use of natural light ( United Nations Industrial Development Organization, 2017). During the production of the football, the most significant energy source is attributed to manual labor, which creates little to no waste. Once the football is ready for distribution, how is it distributed, and how does transporting materials throughout the production create waste?

Let's look at the role transportation plays throughout the production process of the Wilson football. First, hides are transported by truck from a farm in Ohio to a tannery in Chicago. After the leather is processed, it is then shipped by truck back to a factory in Ohio. Then footballs will be shipped, by truck or train, to a retail store or to a football team. Although we cannot know the exact amount of emissions created by the transportation of Wilson footballs, it is estimated by a study done by the United Nations Industrial Development Organization that a truck transporting leather can release up to 60 to 150 grams of CO2 per metric ton of freight and kilometer of transportation. A train transporting leather can produce 30 to 100 grams of CO2 emissions. Isn't it incredible that the entire process begins and ends in Ohio, but not the entire process occurs there. The role of transportation in creating waste cannot be underestimated.

Finally, we will analyze the effect of Wilson footballs once they near the end of their life cycle, usually in a landfill. As mentioned at the beginning of this analysis, leather itself is slowly biodegradable, and treatment of different chemicals during the tanning process makes it resistant to chemical, thermal, and microbiological degradation (Dixit, S., Yadav, A., Dwivedi, P. D., & Das, M. (2014). However, according to the article, "How do you recycle old sports balls?", a well-made ball can last up to 15 years before showing signs of distress. Wilson recommends that consumers should use certain products to maximize the life of their ball. These include soap and warm water,tack spray, tack bar and ball conditioner( sourced from the processes used by Horween) as well as a ball brush and mud (Lena Blackburne rubbing mud; a silt-based mud that won’t scratch the leather.) However, according to "How do you recycle old sports balls?",once the ball does reach the end of its life leather factories often accept cleaned leather that can be shredded and reformed, and recycled rubber is bound with a rubber agent to create new items like wallets and belts. The rubber bladder inside the football can also be used to make new footballs. Nowadays, consumers even turn balls into other useful products like handbags. Having said that, the fate of a game of football is different; these are usually bought by collectors and spend the rest of their days on display or in a box in someone's basement.

Through careful analysis of each part of the process of producing a Wilson football, we learn that the environmental impacts of a football are much more significant than we may have previously imagined. From obtaining primary materials, to processing secondary materials to machine usage, and distribution, the effects of waste and pollution are quantifiable. Although the effects do not seem severe when compared to the production of other products, a change to more sustainable materials and processes could help create a more environmentally friendly football and sport. The fact that much of the labor is still done manually is incredible and helps maintain lower energy consumption. Overall it is interesting to learn that the same industries have been involved in football production for over 100 years. It is undeniable that the quality of the craft is to the highest degree. However, as we enter a new era, these companies may need to rethink how they can do their part in creating a more sustainable future.

Fig. 1. Advanced technological options for leather processing

(Dixit, S., Yadav, A., Dwivedi, P. D., & Das, M. , 2014)

Fig. 2. Environmental impact of leather industry and technologies to combat the threat

(Dixit, S., Yadav, A., Dwivedi, P. D., & Das, M. , 2014)

Bibliography

CAMPBELL Lockstitch Sewing Machine. Campbell Randall. (n.d.). Retrieved March 10, 2023, from https://campbell-randall.com/product/model-campbell-lock-stitch

Developer. "How a Football Is Made - the Football Manufacturing Process." W.N. Shaw, September 10, 2018, https://wnshaw.com/how-a-football-is-made/.

Dixit, S., Yadav, A., Dwivedi, P. D., & Das, M. (2014). Toxic hazards of leather industry and technologies to combat threat: A review. Journal of Cleaner Production, 87, 39–49.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0959652614010580

"Football (Ball)." Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, February 5 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Football_(ball)#Gridiron_football.

"Football." How Products Are Made, MadeHow, http://www.madehow.com/Volume-3/Football.html.

Golden, Jessica. "Inside the Football Factory That Powers the Super Bowl." CNBC, CNBC, January 28, 2015, https://www.cnbc.com/2015/01/28/inside-the-football-factory-that-powers-the-super-bowl.html.

Harriet. (2020, December 2). Introducing strap: The World's first 100% Compostable sports tape. Digital Sport. Retrieved March 8, 2023, from https://digitalsport.co/introducing-strap-the-worlds-first-100-compostable-sports-tape

Hoefs, Jeremy. "Materials Used for Footballs." SportsRec, 15 Oct. 2019, https://www.sportsrec.com/84754-materials-used-footballs.html.

How do you recycle old sports balls? rookieroad.com. (n.d.). Retrieved March 5, 2023, from

https://www.rookieroad.com/sports-equipment/how-do-you-recycle-old-sports-balls-1551657/

How to prep A football like the Pros. Wilson Sporting Goods. (2022, September 8). Retrieved March 13, 2023, from https://www.wilson.com/en-us/blog/football/how-tos/how-prep-football-pros

JS-203 upper steam softening machine. JSM Auto. (n.d.). Retrieved March 8, 2023, from https://www.jsmauto.com/en/product-item/js-203-upper-steam-softening-machine/

Kahler, K. (2019, January 31). Super Bowl 2019: How cows become NFL footballs - sports illustrated. From Farm to Field, and Every Point Between: How a Cow Becomes a Football. Retrieved February 24, 2023, from https://www.si.com/nfl/2019/01/31/how-cow-becomes-football-horween-wilson

Kelly, Roger. "The Making of an NFL Football Is a Time Honored Process." American Football International, February 4 2015, https://www.americanfootballinternational.com/making-nfl-football-time-honored-process/.

Kral, I., Buljan, J., & Hochwallner, S. (2017). (rep.). (H. Beachcroft-Shaw, Ed.)Leather Carbon Footprint . United Nations Industrial Development Organization . Retrieved 2023, from https://leatherpanel.org/sites/default/files/publications-attachments/leather_carbon_footprint_p.pdf.

"Manufacturing Process." Wilson Football Commodity Chain, The Ohio State University , Dec. 2015, https://u.osu.edu/wilsonfootballcommoditychain/manufacturing-process/.

McCuhil, F. (2012, August 6). How to calculate the electrical cost of an Air Compressor. Quincy Compressor. Retrieved March 9, 2023, from https://www.quincycompressor.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/how-to-calculate-the-electrical-cost-of-an-air-compressor-1.pdf

Mohsenirad, B., & Fataei, E. (2020). Life cycle assessment of ball bladder production with and without recycled rubbers. Journal of Advances in Environmental Health Research, 9(3), 183–190. https://doi.org/10.32598/jaehr.9.3.1184

Monmouth Rubber & Plastics. (2021, November 28). Is nitrile butadiene rubber a sustainable product. Monmouth Rubber & Plastics. Retrieved March 8, 2023, from https://monmouthrubber.com/is-nitrile-butadiene-rubber-a-sustainable-product/

Singh, Vijai, and Ashley Maas. Inside a Wilson Football Factory. YouTube, The New York Times, January 22, 2015, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BVOyf3Dc_WY. Accessed February 8, 2023.

Smith, Mark. "How to Make an NFL Football: History, Material, Design." Stabene, March 28, 2019, https://stabene.net/how-to-make-nfl-football-history/.

"Take a Look inside the Plant Where Football Leather Is Made with NFL Player Israel Idonije." The United Food & Commercial Workers International Union, UFCW, February 11 2022, https://www.ufcw.org/football/.